Self-Study [n]. The collection of evidence that COA-accredited organizations put together prior to their Site Visit that shows how they are implementing best practice standards.

We at COA know that generating the Self-Study is a both a challenging and enlightening process for organizations, and we regularly hear from about the value that it brings even after achieving accreditation. That got us thinking; we wanted to dig deeper to find out how organizations were continuing to leverage their Self-Studies after the accreditation process was complete.

In March 2020, we put out a call for organizations to share all the ways that the Self-Study lives and continues to impact their organization beyond accreditation. We partnered with the Alliance for Strong Families and Communities (the Alliance), one of our founding Sponsoring Organizations, who maintain a library of Self-Studies that are accessible to their members. It was wonderful to see the second lives that Self-Studies take on, helping organizations to continue grow and thrive by informing a wide range of functions. And no, using the Self-Study (which can be quite a large collection of evidence) as a doorstop or flyswatter was not mentioned.

The Alliance Self-Study Library

The Alliance Self-Study Library is a valuable resource for member organizations, providing a wealth of information and documentation. The library contains approximately 3,500 COA Self-Study documents and 66 Self-Studies from member organizations, with confidential information removed before archiving. All materials are digitally archived, and documents can be pulled for member requests.

The Self-Study Library can be helpful for Alliance members completing their own Self-Studies, or for developing policies and procedures for their own organizations. Organizations have also used the information for creating job descriptions, developing strategic or fundraising plans, and board books – giving members insights into how other organizations have strategized or used resources in innovative ways. If you are a member of the Alliance, please e-mail the library with any questions or to submit your Self-Study documentation.

Now on to our survey results…

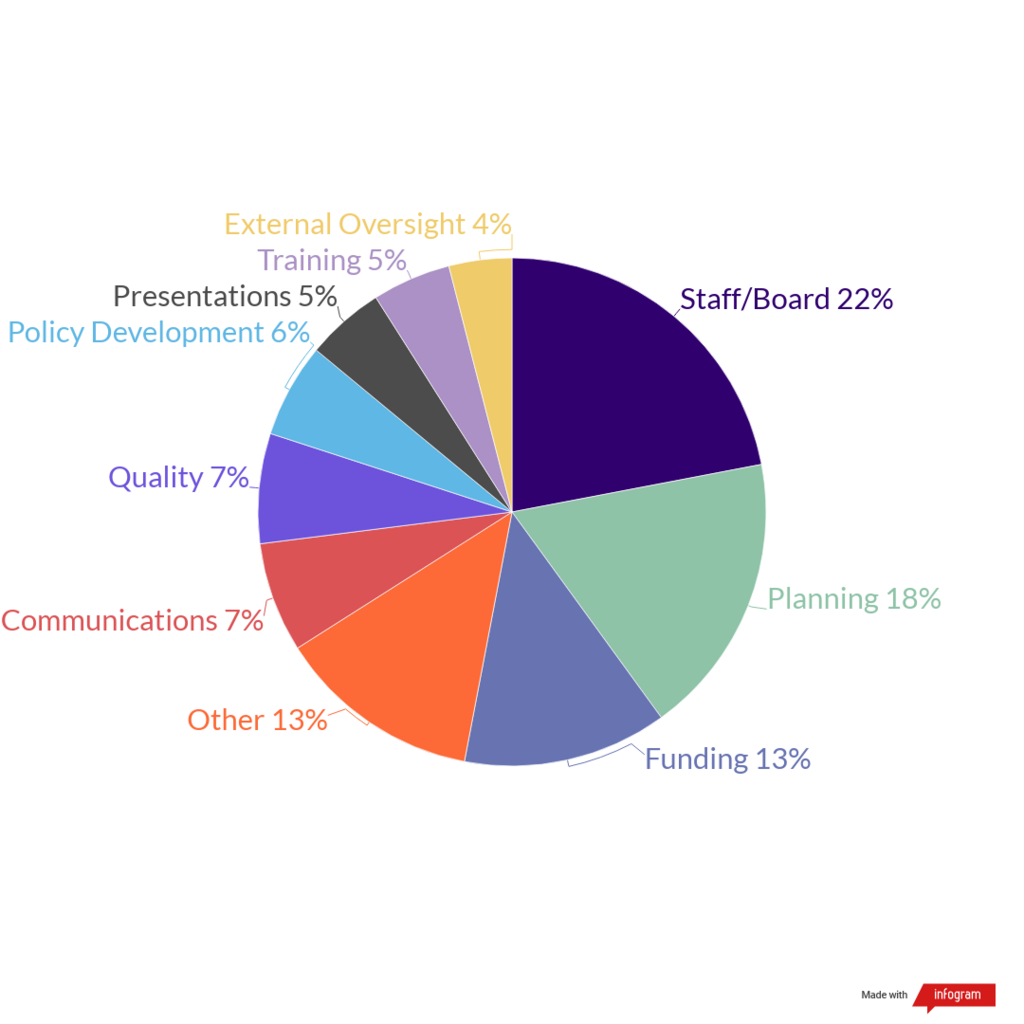

How organizations reuse their Self-Study

We received more than 50 individual uses of the Self-Study from COA-accredited organizations in the United States and Canada. 22% were focused on providing information to internal staff and board members. More specifically, organizations use them for orientations and manuals/resource development. A couple of organizations even use them as trivia fodder when preparing for Site Visits – or during team building or staff activities – to showcase how well employees know the organization. The Self-Study has been described as the go-to document that many people look for when starting at a new organization, because it provides a comprehensive look into the organization itself and gets them up to speed quickly.

“There is nothing that should be outside the accreditation process, as the accreditation process encompasses everything we do.”

-Survey respondent

On the planning-side, 18% of responses focused on the Self-Study as a planning resource. In particular, organizations use it for strategic plan development, including providing it to planning consultants when working with external partners.

13% of responses focused on funding-related uses for the Self-Study. Organizations noted that it helps to open up funding opportunities, since it documents the high standards of services that they are providing. The Self-Study information also helps to facilitate the completion of grant applications and informs reporting to large funders.

“It’s a great reference tool for grant applications. Sometimes I’ll recall something I wrote in the Self-Study that perfectly fits a question in a grant application.”

-Survey respondent

The Other section (13%) provided some very interesting ideas for Self-Study uses we hadn’t thought of. This included using them in social work-focused higher education, where an anthology of Self-Study documents could be analyzed for a leadership or organizational structure class. For organizations that are considering accreditation, it helps them to become more familiar with the process and the importance of looking at the whole organizational structure. Outside of accreditation, reviewing the Self-Study of an established organization can also serve as a reference guide for newly formed organizations as it helps to inform best practices. Accreditation Site Visits are not the only visits, audits, or other reviews that organizations are faced with, and the Self-Study can help to prepare for these.

“[The Self-Study] is a great way to keep the organization accountable to administrative areas that may fall through the cracks otherwise (especially in HR and PQI).”

-Survey respondent

The use of the Self-Study to inform communication strategies (7%) and outreach was another interesting way organizations leverage the Self-Study information. Organizations use their Self-Study to inform their website content, external marketing materials (in particular the narratives), their newsletters, and materials distributed to their volunteers. It is also a useful tool for communicating with government officials about how their decisions inform the work that organizations conduct.

The Self-Study also plays a role when it comes to quality improvement. 7% of organizations use it to help program directors begin to identify areas for improvement, learn more about best practices, and improve upon an agency’s policies and procedures. These organizations recommend that it should be shared with both internal and external stakeholder to demonstrate continuous quality improvement.

“The Self-Study document should be a living document that is part of a continuous quality improvement process.”

-Survey respondent

To round out the uses, policy development was cited as a Self-Study use by 6% of organizations. This applies both internally and when developing policies with community partners. 5% of organizations use the Self-Study for both presentations and training. Presentations included those for stakeholders, donors, and other audiences that desire data-focused content. Trainings focused more on using the Self-Study information for internal staff trainings. Lastly, 4% of organizations noted using the Self-Study to support external oversight or licensing visits, as was alluded to in the “other” section.

“We’ve used our Self-Study during agency audits and monitoring site visits. It’s a great ‘vault’ of information on our governance and organizational structure, quality improvement activities and risk management practices.”

-Survey respondent

Conclusion

As you can see, the Self-Study’s usefulness does not end after an accreditation decision. It is the informational heart of an organization, one that can provide easy access to key information to help with everything from staff and board engagement to strategic planning and securing funding.

Thank you to all of you who took the time to share your own experiences. If you did not get a chance, please feel free to add a comment below and let us know how you use yours!

Since we began taking huge societal steps to flatten the curve and address our current public health crisis, my inbox has been flooded with emails from what seems like every retailer and restaurant I have ever visited. Are they reaching out to alert me of the latest sales or entice me with a great deal? No. These businesses are reaching out to inform me about their individual response to the spread of COVID-19. These communications have included how they are adhering to state-specific closure orders, enhancing their hygienic practices, supporting the health and safety of staff, and pretty much anything related to changes brought on by measures to combat the spread of COVID-19.

Social service providing organizations, whether classified as essential or nonessential during this time, are no different in that they must strive to communicate with their stakeholders about how they are addressing COVID-19 as an organization. Across a single social service program, stakeholders can include clients, family members of clients, staff, volunteers, community members, funders, and board members. All of these stakeholders can be impacted in different ways by your COVID-19 response measures. Communicating clearly and specifically to individual groups of stakeholders will show them that your organization is taking the crisis and its role in protecting the community seriously.

COA has put together a list of references to assist your organization in navigating communication with your stakeholders during this time. We’ve organized the information below by:

- Developing a communication strategy

- Staff outreach

- Funding, media, and advocacy outreach

- Materials

- Guidance on reducing stigma

Our Interpretation blog is meant, first and foremost, to be a resource for the COA community. We are continually evolving its content to meet the needs of our COA network. If you have a resource, article, or tool that you’d like to see posted, we’d love to hear from you! Reach out to us by email at PublicPolicy@coanet.org.

Developing a communication strategy

The abrupt transitions required by COVID-19 has forced for-profit and nonprofits alike to rapidly address a myriad of issues, including communication with their stakeholders. Taking the time to develop a planned communication approach will ensure there is continuity and comprehensive information in your communications and will likely prevent time spent later answering questions. Harvard Business Review has published some helpful tips in developing your communication approach, beginning with the creation of the standing Pandemic Leadership Team. They have also examined the emergency communication responses of companies that have experienced crises previously.

- Harvard Business Review: Communicating Through the Coronavirus Crisis

Staff outreach

Whether your agency staff are considered essential or non-essential workers, it’s important to understand that they are impacted both professionally and personally by this crisis. Communications to staff should be sensitive to this by providing clear, concise, and accurate information. In addition, ensure staff are given a supportive and facilitative environment to ask questions and seek clarification. Workers are dealing with a myriad of concerns as a result of COVID-19. They’ll expect clear information regarding everything from individual health insurance coverage to expectations in work-from-home policies.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has created tools to assist employers in communicating about COVID-19 with their staff. In addition, Forbes has put together a survival guide to caring for staff in a remote environment that can help you craft internal communications during this time. How you communicate with staff during this crisis will dictate the office culture when you return.

- CDC: Prepare your Small Business and Employees for the Effects of COVID-19

- Forbes: Company Survival Guide To Care For Staff During The Coronavirus Pandemic

Funding, media, and advocacy outreach

Addressing the global public health crisis has led to an unprecedented global financial crisis. Legislators at the state and federal level are working hard to determine how best to support the economy while maintaining needed social distancing precautions.

The first federal stimulus package, the Families First Coronavirus Response Act, provided some of the financial aid needed by businesses and individuals. It is expected to be followed up with subsequent stimulus bills to continue providing meaningful aid. This means there will be additional opportunities for service providing agencies to advocate for inclusion in future relief packages. It is important that agencies are using any and all tools and connections they have to advocate for their stakeholders and raise awareness of the importance of their specific services in their community.

The Alliance for Strong Families and Communities (also known as the Alliance) has created a toolkit for their network to raise awareness about the importance of community-based human services organizations, which become even more vital in times of crisis. To also assist you in raising critical funds, this toolkit includes a national fundraising campaign with graphics and sample posts, as well as media outreach templates. Use these tools to leverage your visibility as part of the national Alliance network and raise awareness for your specific community impact and financial needs.

- Alliance for Strong Families and Communities – COVID-19 Fundraising and Media Outreach Toolkit

Materials

Communicating accurate and helpful information is the duty of all organizations addressing COVID-19 in their community. On-site, this can mean having materials available to service recipients. The CDC and the World Health Organization (WHO) have published a number of free resources for all businesses to use, including fact sheets, guidance, videos, and posters. By using the latest materials published by the CDC, you will ensure the information you are communicating is in accordance with current public health announcements and guidance. In addition, check your state’s public health and human service department’s departments websites to see if materials specific to your state are available to you. Below are links to current communication tools and resources available for use and distribution.

- CDC: Communication Resources

- CDC: Directory of state and territory health agencies

- WHO: Communicating the Risks of COVID-19

Guidance on reducing stigma

Stigma affects the emotional and mental health of those that the stigma is directed against. Stopping stigma is an important part of making communities and community members resilient during public health emergencies. Even if we are not personally involved with the stigmatized groups, it’s important to stay vigilant and address it when issues arise.

We hope you find these resources useful! Check out our other posts on COVID-19—COVID-19 Resources (Extended Version) and Preparing for Response to COVID-19,—for additional information.

What other helpful resources for managing communication during the COVID-19 outbreak have you seen? Share yours in the comments below!

In light of the ongoing coronavirus crisis, we wanted to highlight some of the resources that we provide on our website, and to provide additional ones, as well. Stay up-to-date on everything happening with COA during the pandemic here.

No matter what role you occupy in the social service delivery continuum, chances are that precautions in the face of COVID-19 have drastically changed the way you work in just a few short weeks. This rapid transition in our lifestyles has led to a deluge of information about how to cope and behave during this time, both personally and professionally. COA has put together a list of references to assist you and your colleagues in navigating all of this news and guidance. We’ve organized the information below by topic:

- General guidance from government agencies

- Guidance for child welfare providers

- Guidance for childcare providers

- Guidance for businesses and employers

- Guidance for healthcare professionals

- Guidance for community organizations

- Guidance on reducing stigma

The Interpretation blog is meant, first and foremost, to be a resource for the COA community. We are continually evolving our blog content to meet the needs of our COA network. If you have a resource, article, or tool that you’d like to see posted, we’d love to hear from you! Reach out to us by email at PublicPolicy@coanet.org.

General guidance from government agencies

It’s important to educate yourself on and follow the guidance of international, national, and local health organizations. The following organizations maintain a collection of resources and information on the spread of COVID-19. COA recommends locating the health agency of your state or territory to find information that is specific to your local community. In addition, make sure that you are signing up for available subscription/distribution lists, where information may be disseminated on an ongoing basis.

- From the World Health Organization (WHO): Coronavirus Disease (COVID-2019) Situation Reports

- From the U.S. Center for Disease Control (CDC): Coronavirus Disease 2019

- From the Canadian Department of Health: Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): Outbreak Update

- Directory of state and territory health agencies

Guidance for child welfare providers

The US Children’s Bureau shared this letter with the agencies they oversee the in child welfare system. In addition to this letter, the Children’s Bureau is maintaining this webpage with resources related to COVID-19.

Organizations leading the field in child welfare practice and policy have also created resources to assist agencies in navigating service delivery during this time:

- From the National Child Traumatic Stress Network: Parent/Caregiver Guide to Helping Families Cope with the Coronavirus Disease

- From Generations United: COVID-19 Fact Sheet for Grandfamilies and Multigenerational Families

- From Prevent Child Abuse America: Coronavirus Resources & Tips for Parents, Children & Others

- From the National Association of Social Workers: Resources for Social Workers

In addition, The Chronicle of Social Change (now The Imprint) has redirected their reporting to focus on COVID-19 and have posted a number of stories on developments in the child welfare space. We recommend starting with Coronavirus: What Child Welfare Systems Need to Think About.

Guidance for childcare providers

Childcare providers have been deemed essential workers across many regions, even areas with the strictest social distancing regulations in place. This is because we need to ensure childcare is accessible to other essential workers during this time.

Guidance for businesses and employers

There is no doubt that concerns about and restrictions around COVID-19 are impacting how businesses are run. We’ve seen some guidance on how to bear out these changes here:

- From the CDC: Resources for Businesses and Employers

- From the US Department of Labor: COVID-19 Overview

- From the National Council on Nonprofits: The Nonprofit Community Confronts the Coronavirus

Guidance for healthcare professionals

Healthcare facilities are on the front lines of the COVID-19 pandemic. Find resources to help manage resources and protect yourself and your staff below.

- From the CDC: Resources for Clinics and Healthcare Facilities

- From the CDC: Resources for Healthcare Professionals

Guidance for community organizations

Community-based organizations will be integral to ensuring the infrastructure of community needs are able to be met during this time. Fortunately, there are COVID-19 tools available for organizations that serve vulnerable populations:

- From the CDC: Resources for Community- and Faith-Based Leaders

- From the CDC: Resources to Support People Experiencing Homelessness

The National Coalition for Homeless Veterans also has resources specific to each type of services provider they oversee:

- From the National Coalition for Homeless Veterans: COVID-19 Resources

Guidance on reducing stigma

Stigma affects the emotional and mental health of those that the stigma is directed against. Stopping stigma is an important part of making communities and community members resilient during public health emergencies. Even if we are not personally involved with the stigmatized groups, our voice can have an impact.

- From the CDC: Reducing Stigma During a Public Health Crisis

What other helpful resources for managing the COVID-19 outbreak have you seen? Share yours in the comments below.

Did you know? In our more than forty-year history, the Council on Accreditation (COA) has only had three logos—the most recent being the COA shield that launched in 2012 (which was an adaptation of a 2002 version). So, we thought with all the excitement surrounding our 2020 Edition standards, coupled with welcoming our new president and CEO, that the time was right to give our branding a refresh.

It was not something that we took lightly and many, many months of planning and design went into getting it just right. We wanted to make sure that we were remaining true to our roots, but elevating the look and feel to be more fresh, modern, and meaningful.

Welcome to the new COA!

Behind the logo

The logo focused on two key areas: the mark and the color palette.

The mark is now a more abstract symbol, shifting the focus from us and refocusing priority on the work and the organizations we support. If you look closely, you will notice that the ribbon—a symbol of achievement and excellence—is comprised of the letters C-O-A. This is meant to evoke feelings of pride and is open to individual interpretation. Some see a doorway or hallway, signaling a journey, process, or movement—much like our accreditation process itself.

Color your world

We utilized color theory to help us find the perfect palette that would not only be pleasing to the eye, but also rich in meaning and emotion. We landed on a light blue to purple gradient, which adds excitement and a sense of modernity…but there is so much more to it. Purple, a non-dominant color, signifies mastery and excellence, but also compassion. Blue evokes feelings of trustworthiness, wisdom, serenity, peace, and security. Combined, they perfectly convey our mission and purpose, while representing strong ties to our founding organizations and service areas.

Engage. Empower. Evolve.

We have also, for the first time, incorporated a tagline into the mix: Engage. Empower. Evolve. This tagline is a nod to our past while looking towards the future.

Engaging organizations as partners is a fundamental part of our DNA. We empower organizations to be efficient and effective so they can provide best-in-class services to the clients and communities they serve. Accreditation is also not a final destination or an end to a means. It’s an evolution. We continually push organizations to evolve and improve.

So, when you put it all together, the tagline truly speaks to our approach to organizational accreditation. Not to mention alliterations are fun!

Extra, extra! New credentialing seal

We realize achieving accreditation isn’t easy—it’s a true accomplishment. We wanted to give organizations a way to signal that they are COA accredited and show off their hard work and commitment to excellence. That is why we developed a special credentialing seal for accredited organizations use as a beacon of their accomplishment (rather than just using our logo).

The seal can be used across all organizational collateral (business cards, letterhead, e-mail signatures, etc.). Accredited organizations interested in learning more about acceptable use can request our new promotional toolkit, which we’ll link to on the launch of our new website.

Thank you

Thank you for being part of the COA community. We hope you are as excited by our new look as we are! Please excuse any materials with our previous logo that you might come upon as we work on getting everything switched over; we are working hard to get the updates your way.

Should you have any questions regarding the use of the seal or COA logo, please do not hesitate to reach out to Kelsey Risbrudt at krisbrudt@coanet.org.

To plan or not to plan? On a personal level, planning is an essential aspect of everyday life. What do I need to get done today? This week? This month? In many ways, planning helps us prepare for the challenges and tasks that may lie ahead. Think of the to-do lists that you make. Whether you physically write tasks down, use an app to organize your to-do’s, or arrange them in your mind, you are planning what needs to get done. In a sense, you are mapping out your future by addressing things that require your attention in the present. It stimulates your mind to embrace the future and envision yourself doing something to reach a desired result. Planning is a necessary activity in setting goals for yourself.

For human service organizations, whether small or large, planning is equally essential. As an organization that provides goods and services to individuals and families with varying levels of need, it is imperative that forecasting is done. This helps to create a roadmap for the direction in which the organization is headed. This is where long-term planning comes in.

Strategic planning, which is synonymous with long-term planning, is about establishing goals to sustain the future of human service organizations. Why is it called strategic planning? Strategy is the operative word from which strategic is derived. Historically, strategy was associated with the appointment of a general in the military to provide guidance on defeating enemies within battle. To serve as an advisor, many things had to be considered, including the size of the opposing army, weaponry, level of skill, landscape at battle locations, etc. in order to develop a winning strategy. Essentially, knowledge on competing factors had to be gathered to make informed decisions about next steps.

Strategic planning for nonprofit organizations follows a similar concept. Since the late 20th century, strategic planning has been used in the nonprofit sector to gather knowledge in order to determine strategy for advancing an organization’s mission. While creating a strategic plan involves levels of complexity and can be overwhelming to think about, it is critical to have a process in place for developing the plan.

Some people ask, “why should we establish a multi-year plan, when organizations are working under the pressures of an ever-changing economic, social and political climate?” While this may very well be true, in the words of Yogi Berra, “if you don’t know where you are going, you might wind up someplace else.” Human service organizations need something to which they can ascribe and push themselves to continuously evolve for the purpose of fulfilling their missions. So, if the organization is operating in a fast-paced environment, strategic planning supports the need to stay on a particular course rather than change paths so frequently that the direction in which the organization is headed is not clear to anyone within the organization.

Strategic planning is about creating a strategy where the end product is a long-term plan to be implemented over the next four years, at minimum. It isn’t just about identifying broad goals to be realized, but also key strategies for how the organization will meet those goals. The traditional strategic planning methodology involves getting feedback from different internal and external stakeholders, such as staff, clients, and community partners; obtaining information on the environment, such as with a community needs assessment or environmental scan; and conducting an analysis of the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (SWOT) of the organization. Many organizations tend to omit a SWOT analysis from their strategic planning process; however, it is beneficial because it provides an assessment of the internal (strengths and weaknesses) and external (opportunities and threats) landscape. Since the strategic planning process includes perspectives from various types of stakeholders, an organization can incorporate feedback in these categories to inform strategic decision-making. Mind Tools, Inc. offers some great resources on conducting a SWOT analysis.

As is the case with for-profit organizations, typically the owners, board members, and leadership in nonprofit organizations lead the strategic planning process. Strategic planning is a critical activity within human service organizations because it provides a sense of direction in which the organization is headed.

If my organization develops an annual plan, should we still develop a strategic plan?

To put it simply, yes. Your organization should still create and implement a strategic plan, even if annual plans are developed; each plan has a different purpose.

The strategic plan identifies the framework for the organization on how to build and sustain programming over time. Should the organization pursue a new funding stream, provide new services aligned with its mission, adopt a trauma-informed model? The strategic planning process allows the organization to determine ways to advance its mission and consider the resources needed to do this. If the organization wants to build a new, state-of-the-art training facility, the strategic plan would include strategies to secure funding, such as a capital investment grant.

The annual plan can include goals that are directly or indirectly related to the strategic plan and are specific to the department or program. So, essentially, the strategic plan influences the annual plan; it is usually not the other way around. Annual planning is largely connected to the budgetary approval process for the next fiscal year. Therefore, it usually involves department and program directors since they project anticipated revenue and expenses, and ways the department is expected to grow. For the annual plan, organizations need to consider where they want programs to be within the next year and the strategic priorities shape those annual goals. Does the organization want to increase the number of clients served by 15% or offer support groups to survivors of human trafficking? The annual plan is operational and considers the daily tasks needed to run a program or department. If one of the organization’s strategic goals is to provide trauma-informed care to clients in all 3 counties where services are provided, then providing new support groups to trafficking survivors seems more closely aligned with the organization’s strategic plan than increasing the number of clients served in programs. This is an example of how an annual plan goal is supported by a goal outlined in the strategic plan. The strategic plan should guide the organization’s yearly objectives.

In order to successfully implement both strategic and annual plans, the organization should identify opportunities to track progress over time. Establishing clear metrics to demonstrate whether goals have been accomplished allows the organization to periodically verify implementation of either type of plan. Determining how progress is measured is equally as important as developing the plan and should be outlined within procedures. Once a clear mechanism has been established, it should be outlined in the strategic and annual planning procedures.

Benefits of strategic planning

- Provides a roadmap to stakeholders on organizational advancements

- Fosters a mission-driven culture within the organization

- Demonstrates a commitment to excellence

- Engages staff in forward-thinking

- Advances the impact of fulfilling organization’s mission

Benefits of annual planning

- Establishes short-term gains to enhance programming

- Provides a deeper connection to the strategic plan

- Reinforces the mission of the organization in daily practice

- Gives staff a clear direction on their responsibilities within the program/department

So, back to the original question, to plan or not to plan? If you are likely to plan out your day, week, or even the next month, hopefully, you see the value in planning the priorities for your organization over the next year and especially how the next several years could potentially look. In addition to creating an opportunity to explore new avenues for the organization, strategic and annual planning can foster a sense of hope in your staff about what may be on the horizon for your organization, despite all the external pressures that organizations continuously face.

A few resources

- National Council for Nonprofits strategic planning tools

- Strategic Planning for Nonprofit Organizations: A Practical Guide for Dynamic Times by Michael Allison and Jude Kaye

- Example of strategic and annual plans and how they interact:

Since Congress passed the Family First Prevention Services Act (FFPSA) in February 2018, stakeholders across the U.S. have been working to maximize the opportunity posed by this tremendous reform to our child welfare system. To ensure that children and families reap the positive benefits of FFPSA, service-providing agencies, social workers, child welfare officials, accrediting bodies, policy makers, and advocacy organizations have been rigorously planning for implementation, all while trying to keep up-to-date on the latest guidance and policy.

Looking for an FFPSA 101? Watch our informational video.

As COA began working with service providers impacted by FFPSA, we found that organizations were not only interested in information about the accreditation process, but also resources relevant to the larger scope of FFPSA provisions. That’s why we created the COA FFPSA Resource Center, a hub of FFPSA-related content including federal guidance, tools and resources, accreditation information, events and trainings, and news.

We are continually evolving the website as new guidance and/or policy is released and as states move forward with implementation. Have a resource, article, or tool that you’d like to see posted on the Resource Center? We’d love to hear from you! Reach out to us by email at PublicPolicy@coanet.org.

Just starting to peruse the site and not sure where to start? Fear not! We’ve created a list of 5 helpful resources to get you started.

1. Federal Requirement Comparison: QRTP and PRTF

From the Building Bridges Initiative

With the support of the Annie E. Casey Foundation, Building Bridges created this comparison to assist providers in understanding the federal requirements set forth for Qualified Residential Treatment Programs (QRTP) and Psychiatric Residential Treatment Facilities (PRTF). The information is organized in a table by requirement component, so that readers can do a line-by-line comparison of each program’s respective requirements. Though QRTPs and PRTFs have some similarities, these programs were created and defined separately in federal law in order to establish varying levels of care for children and youth with significant behavioral health needs.

Building Bridges is a national initiative working to identify and promote practices and policies that will create strong coordinated partnerships and collaborations between families, youth, community- and residentially-based treatment and service providers, advocates, and policy makers to ensure that comprehensive mental health services and supports are available to improve the lives of young people and their families.

2. Responsibly Defining Candidacy within the Context of FFPSA: 5 Principles to Consider

From the Center for the Study of Social Policy

The Center for the Study of Social Policy created this brief of guiding principles for states to consider as they work to identify a definition of foster care candidacy that fits within the context of their state policies and prevention service array.

FFPSA defines the term ‘child who is a candidate of foster care’ to mean “a child who is identified in a prevention plan under section 471(e)(4)(A) as being at imminent risk of entering foster care…but who can remain safely in the child’s home or in kinship placement as long as services of programs specified in section 471(e)(1) that are necessary to prevent the entry of the child into foster care are provided” (Sec. 50711). This means each state will be responsible for defining candidacy in their State IV-E Plan, which will be submitted to the Children’s Bureau. State definitions of “candidacy” will be extremely important in deciding which children and families will be served under FFPSA prevention services. This resource provides a guiding methodology for state policymakers in creating that definition and assists in considering the way such a policy will impact children and families in their state.

3. Program Standards for Treatment Family Care

From the Family Focused Treatment Association (FFTA)

As we learn more about the impact that FFPSA implementation will have, it has become clear that there is a need to bolster the continuum of child welfare services offered to meet the needs of children and families. Treatment Family Care (TFC), also known as Treatment Foster Care (TFC), has emerged as a leading service to meet the behavioral needs of children in home-settings rather than residential care. The strict parameters established around residential placement under FFPSA puts a spotlight on TFC as a service that can maintain a residential level of care while keeping children and youth in a home-setting.

Though TFC services are provided across the country, federal guidance related to funding opportunities, practice standards, and program oversight has never been issued. Fortunately, Congress is currently considering the Treatment Family Care Services Act (HR3649 and S1880), which will provide states with a clear definition and guidance on federal TFC standards under the Medicaid program and other federal funding streams. This clarification will promote accountability for states offering TFC, support FFPSA implementation, promote appropriate TFC services for reimbursement, and drive personnel training and standards.

FFTA first published their own Program Standards for TFC in 1991 to define the model and set parameters for the field. In 2019, FFTA published the revised 5th edition, which provides several updates to the previous edition and in particular approaches the standards from a broader perspective of Treatment Family Care. This is in response to the changing needs of children, youth, and families; programmatic changes; and service expansions impacting TFC services. In particular, the new edition expands the view of TFC by integrating a focus on children living with kin. This inclusion was necessitated by an increasing expectation to meet the treatment needs of children in kin settings, stemmed by the belief that living with family can minimize the trauma associated with separation from parents.

View the FFTA’s program standards here.

4. Title IV-E Prevention Services Clearinghouse website

From the U.S. Administration for Children and Families (ACF)

The Title IV- E Prevention Services Clearinghouse was established in accordance with FFPSA by the Administration for Children and Families (ACF) within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Its goal is to conduct an objective, rigorous, and transparent review of research on programs and services intended to support children and families and prevent foster care placements. Programs submitted to the Clearinghouse are rated as “well-supported”, “supported”, “promising practice”, or as “not meeting criteria”. The initial programs that have been rated include mental health services, substance abuse prevention and treatment services, in-home parent skill-based programs, and kinship navigator programs.

Ratings will help determine programs’ eligibility for reimbursement through Title IV-E funding. The Clearinghouse continues to be updated as new services are reviewed and rated, those interested in receiving real time notifications of updates can sign up here.

Access the Title IV-E Prevention Services Clearinghouse here.

5. National and state FFPSA news

From our FFPSA Resource Center

Implementation of FFPSA will mark the largest reform to our national child welfare system in decades. Since FFPSA passed in February 2018, there have been hundreds of news outlets reporting on the many components of reform at the national and state level, including information on implementation, related legislation, funding opportunities, service delivery, and more. The large scope of provisions can make it difficult to find the information that is relevant to your role in implementing FFPSA. That’s why COA created a FFPSA news round-up, updated regularly with content published related to state-specific activities and national news related to FFPSA.

State-level news can be viewed here and national-level news can be found here. Want to get alerts when important updates are published? Sign up for our mailing list.

We hope these resources will support you and your agency in learning more about the provisions of FFPSA. We would like to thank all of the organizations that have produced content to assist our field with this important legislation.

Though we’ve identified these five resources to get you started, we encourage you to continue your research and explore all of the information available at www.coafamilyfirst.org. And since we couldn’t pick just five…

Bonus resource!

Accreditor Comparison Guide

Needing to pursue national accreditation as a result of FFPSA? The first step is to find an accreditor that is the right fit for your organization. To support agencies in choosing an accreditor, we created a comparison guide that details the differences between the COA, CARF, and JC accreditation processes.

When it comes to serving communities and responding to individuals in crisis, law enforcement agencies and human service systems each play a role in maintaining the safety and stability of their communities. Substance use, child welfare, intimate partner violence, suicide, juvenile justice, mass violence — these are not only some of the most prominent societal challenges we face today, but also circumstances where both police officers and human service professionals are on the front lines.

The roles of law enforcement and human service agencies therefore consistently overlap. In communities and environments where needs are intensified and resources limited, this overlap comes into sharper focus. When behavioral healthcare is inaccessible, or social service systems are overburdened, communities often turn to law enforcement to fill in the gaps — sometimes leading to serious negative outcomes that can inflict trauma, injury, or death:

- Foster youth arrested and handcuffed for running away

- Mental illness played a role in 25% of fatal police shootings in 2017

- Misunderstanding disability leads to police violence

Such incidents are not only harmful to the individuals involved, but can also irrevocably damage a community’s trust in its police force and social support systems. These trends are a clear indicator that communication and partnerships between law enforcement agencies and human service providers need to be examined and strengthened.

Collaborative approaches to crisis intervention

The relationship between behavioral health and policing cannot be overstated; according to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, individuals in mental health crisis are far more likely to be confronted by police than to receive medical attention. More than 90% of patrol officers encounter individuals in crisis, with an average of 6 encounters per officer per month, but officers are often unprepared to meet the unique challenges of de-escalating a person with a disability or mental illness in crisis. A traditional law enforcement approach — “command and control,” — designed for crime intervention is likely to elicit fear and disorientation in individuals with disabilities or who are in emotional distress. Such approaches pose a significant risk of triggering a trauma response and escalating the dangerous behavior, increasing the likelihood for excessive force to be deployed.

In response to these challenges, law enforcement agencies have increasingly recognized the value of diversifying capacity and expanding officers’ skill sets in order to increase safety and efficacy in crisis response. In addition to ramping up efforts to educate officers on trauma, mental illness, and disability, and expanding training on de-escalation and crisis intervention techniques, many departments are adopting innovative new models to partner with behavioral health and human service professionals in police work.

Crisis Intervention Teams are one popular model in use in 2,700 communities across the country. The core components include recruiting, selecting, and training officers to serve as designated responders to mental health crises, and establishing relationships with a designated mental health receiving facility and other resources in the community to facilitate immediate emergency entry into the mental health system and reduce barriers to care. Officers receive 40 hours of intensive training on common disorders, developmental disability, and crisis de-escalation skills. Key to the success of this model are: ensuring adequate staffing to maintain continuous CIT coverage, equipping emergency dispatchers with the skills needed to identify when a CIT response is appropriate, and designing and delivering training curricula with the collective input of law enforcement, behavioral health specialists, and advocates. Evaluation of the CIT model indicates that it yields positive results, reducing officer injuries as well as the need for more intensive and costly law enforcement responses as well as increased referrals to emergency health care and accessibility of mental health services.

Co-responder programs are another partnership strategy with growing interest. Los Angeles, Omaha, Mesa, Arizona, and Huntington, West Virginia are among the jurisdictions that are adopting or expanding programs in 2019 to embed therapists, social workers, or addiction counselors into police departments. There is no standardized model, and program scope varies widely from place to place: some departments hire behavioral health specialists directly while others coordinate part-time or rotating coverage from a local provider; some target suicide and others substance use; they may be first on the scene or “secondary responders”; responsibilities can range from emergency response, community patrol, or even follow-up and case management. Although the programs are incredibly diverse, the rapid rate of adoption points to a culture shift in law enforcement: an emerging understanding of the agency’s role in responding to complex issues facing their communities, willingness and recognition of the value of working closely with human service professionals, and an investment towards diverting individuals in crisis away from the criminal justice system.

Establishing boundaries

Responding to individuals in crisis in the community is not the only circumstance where law enforcement and human services intersect. Although the integration of social workers and therapists into the world of community policing is a growing trend, for many human service providers — especially resource-starved ones — engaging police departments for assistance is standard operating procedure that may come with unintended consequences.

In a May 2019 lawsuit filed against the Administration for Children’s Services, the New York state appellate court ruled that family courts do not have the authority to issue warrants for foster youth who have run away from their placements — a longstanding practice. In 2017, the child welfare agency was granted 69 arrest warrants for children in their care; that was after guidelines for seeking warrants were tightened in 2015, when the number of arrest warrants issued was up to 125. In a majority of these cases, police officers deployed to retrieve missing youth end up putting them in handcuffs and in jail cells, regardless of safety risk.

Runaway behavior in foster care can often be attributed to trauma — children leave their foster care placements to be with the family members from whom they’ve been separated or other loved ones, or due to conflict with their foster parents. Being apprehended and even restrained by police officers and forcibly returned to settings where they may not feel safe exponentially compounds that trauma. The already fragile (or absent) trust in the child welfare agency may be eroded, often irrevocably, and the agency’s motivation may be perceived as punitive vs. protective.

In congregate care, the intensive needs and challenging behaviors of residents can often overwhelm the capacity of personnel and for many residential facilities, a common response to harmful or disruptive behavior, or unauthorized leave, is to summon police officers. In some communities, police departments report responding to struggling facilities multiple times a day. As with crises that take place in the community, the consequences of calling the police can be significant if the appropriate skills and protocols are not in place. And for organizations, chronic reliance on police intervention poses additional risks: therapeutic setbacks to service recipients involved, damaged staff morale, and diminished perception in the eyes of the host community and collaborating providers.

In 2015, California passed legislation aimed at reducing the frequency of law enforcement intervention in group homes and other residential facilities for children and youth. But policy or regulation is unlikely to be effective if the underlying causes are sidestepped. Experts argue that frequent calls to law enforcement are an indicator of deeper issues: inadequate staffing, insufficient training, ineffective programming, or a need to reassess admission/screening criteria. The continuum of challenges endemic to social services — underfunding, understaffing, burnout, turnover — hamper providers’ ability to meet the needs of their service population and maintain a safe and stable therapeutic environment.

If police intervention is unavoidable, then effective collaboration and proper training is critical. Providers and police departments must ensure that responding officers are familiar with the characteristics and needs of the service population and learn the skills necessary to safely de-escalate, retrieve, restrain a service recipient utilizing the least restrictive response to maintain safety. Recommendations from advocates include:

- Jointly evaluating policies and protocols to emergency response

- Creating Memoranda of Understanding between police departments and providers to better define roles and expectations around interventions, and ensure that responding officers are given relevant details about the residents in crisis

- Better data collection and analysis on the frequency and nature of law enforcement intervention in treatment settings

Children’s Village, a COA-accredited provider in New York, has called upon city leaders to form a Runaway Youth Taskforce to bring together law enforcement and social services in developing a new model for preventing and responding to runaway youth.

Meeting the mental health needs of police officers

A recent cluster of officer deaths by suicide has shed a harsh light on the challenges of addressing the mental health needs of the law enforcement community. Officers are at increased risk of PTSD, depression, anxiety, substance use, and suicide due to constant threat of violence or actual violence and exposure to death and trauma, in addition to chronic work stressors such as sleep deprivation and fatigue. Although repeatedly acknowledged by law enforcement agencies and police union leadership, the mental wellness needs of police officers are still persistently unaddressed. The culture of law enforcement has often been cited as a major barrier to care, with officers reporting fear of perception of weakness, alienation from fellow officers, and other potential professional repercussions as a result of seeking out needed services and supports.

Ignoring the mental health of police officers puts communities at risk. Studies have linked PTSD with impaired decision making ability — a critical implication for police officers in potentially life-threatening situations, and the potential for excessive or deadly force. These incidents not only increase the risk of injury or fatality of those involved, but also negatively impact the relationship between the community and law enforcement.

The human services field may be uniquely positioned to make a positive impact in this area. Professional staff in the social services and behavioral health field share many of the same work stressors as police officers — excessive caseloads, exposure to traumatic events, vulnerability in the community or service environment — and the impact of secondary or vicarious trauma has become a prominent area of research and advocacy in the human services field. Providers can bring significant knowledge to the table for law enforcement agencies about identifying and mitigating the effects of PTSD and secondary trauma, appropriate resources for treatment and support, and strategies for bolstering officers’ resilience.

Increasing the presence of behavioral health professionals in law enforcement settings can provide multiple benefits — not only by distributing or diverting the “social work” attributes of community policing, but also by providing an avenue for officers to seek support and referral to available services. Law enforcement leaders might also consider whether services provided outside of the auspices of the law enforcement agency might be more accessible to officers, potentially reinforcing confidentiality of services and softening the impact of stigma. Service providers can also assess opportunities to expand or tailor their service array in a way that focuses on the unmet needs of this population or supports their families. Research suggests that cultural competency — awareness of and responsiveness to the cultural and professional idiosyncrasies of police work — is pivotal to the accessibility and efficacy of psychological interventions targeted at police officers, and may be enhanced through peer-driven program design.

To protect and serve — and partner

Communities today are recognizing that the most pervasive social and public health challenges they are confronted with cannot be overcome without constructive collaboration between the social service, behavioral health, and criminal justice systems. Successful collaboration hinges, however, on meaningful assessment of areas of strength and need, clearly delineated roles and responsibilities, and a shared commitment to invest in the most effective solutions. Many agencies are developing or pursuing creative strategies to build partnerships between providers and police officers, with the understanding that joining forces is imperative to forming a greater understanding and capacity to meet the needs of their shared community, strengthening public trust and improving outcomes across all systems.

We’d love to hear from any organizations with experience in human services – law enforcement collaboration. Please share any promising practices or lessons learned in the comments below.

Learn more or get involved

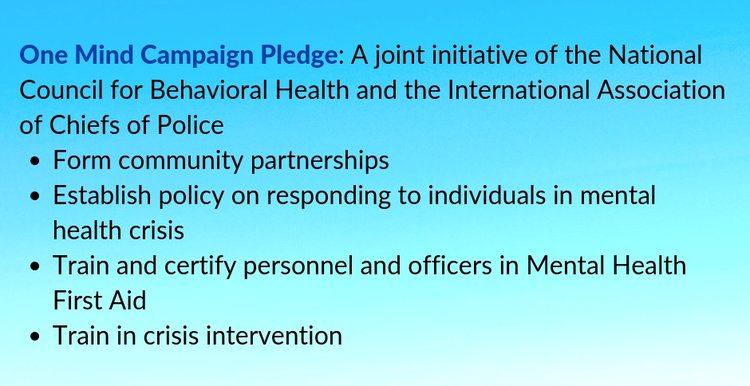

- International Association of Chiefs of Police: One Mind Campaign

- Vera Institute of Justice: Serving Safely initiative

- National Alliance on Mental Illness: Resources for law enforcement officers

Your organization has decided to embark on the journey of pursuing accreditation! This commitment can invoke many sentiments—happiness, anticipation, fear, anxiety, and maybe even a splash of frustration. These are all normal feelings. The accreditation process is a major project with a myriad of components. One way to be successful in your accreditation work is to use a project management approach, as it is critical to divide the required work into smaller, manageable steps. Here is a handy, step-by-step guide you can use to conceptualize the tasks that are on the horizon.

Work styles & organizational culture

COA has an organization-wide accreditation model. This means that not only are programs being reviewed, but also the administrative divisions as well. Getting many colleagues involved in the accreditation process will help the organization manage the workload and focus on developing, updating, or sustaining practices that are ultimately in the best interest of the consumers served.

People have different personalities, which includes varied preferences and approaches to their work responsibilities. There are those who are process-oriented people that do a really great job poking holes in plans and asking questions that may not have been considered. Then there are staff who can reflect and acknowledge the progress that has been made within the organization through that point in time. Knowing some of these characteristics and preferences will be helpful in thinking about who should handle different aspects of the work.

How and why the organization is choosing to pursue accreditation is essential to framing the work that lies ahead. Even if the organization is mandated to achieve accreditation, what the organization hopes to accomplish through this process is valuable for all to hear. Ask yourself: What is the message we will convey to our board, advisory group, staff, consumers, and other relevant stakeholders about what accreditation means for the organization and its future? People want something they can believe in, something that resonates with them, so taking time to reflect and think about the “why” behind this journey is an opportunity to capitalize on building momentum.

Accreditation workload – forming the structure

COA accreditation includes all aspects of the organization’s administration and service delivery operations. There are three types of standards: administration and management, service delivery administration, and service. Most organizations will have at least ten standard sections to review based on the three categories. It is essential to have multiple staff managing different standard sections, because no one staff member will have all the answers (and that is a good thing)!

A question we often hear from organizations is “How will we manage the accreditation work?” You must consider whether your organizational structure serves as a sufficient framework to review the standards. This means that those individuals responsible for particular divisions would delegate tasks to staff within their department. For example, the director of human resources would review the human resources management standard section and assign tasks as needed to his/her staff. Similarly, program directors would follow the same process to review service standard areas.

Another option for managing the work includes the creation of functional work groups, which includes assembling teams with individuals from different departments and/or programs to review one or more standard sections. For example, an administrative work group can be formed to review multiple standard areas including risk management, administrative service environment, ethical practice, etc. This type of work group would include an interdisciplinary team of quality improvement, program, information technology, and other staff as needed.

Decision-making authority and flow of communication

Once a decision is made on whether to use the structural work groups, functional work groups, or a hybrid of the two, the organization must consider the decision-making authority. As teams begin to work on reviewing the standards against current practices, you may find that policies, procedures, and protocols may need to be developed or modified. The organization must be clear on who has the authority to implement new procedures and practices.

Typically, if hierarchical work groups are used, the head of the department or program would be responsible for managing the approval process. Larger organizations may have a chief operations officer or director, and that person may be responsible for final approval. In smaller organizations, decision-making authority may be the sole responsibility of the executive director. In functional work groups, the decision-making authority may be less transparent, so the organization should establish the process for preliminary and final approval of procedures and new protocols. This will be particularly important once staff begin doing the actual work that is part of the Self-Study and Site Visit phases of the accreditation process.

Regardless of the structure chosen to manage the work, the individual responsible for overseeing the accreditation process needs to ensure that work groups and teams routinely provide information and updates to them. Sharing information and progress with the leadership team is a must, especially if the accreditation lead is not a part of said team.

Responsibilities associated with stages of accreditation process

There are six stages in the accreditation process, each with different responsibilities. Below are some salient tasks for which the organization is responsible.

Application & agreement

The application and agreement phase of the process is an opportunity for the organization to assess the cost of accreditation and explore the service standard sections that may be relevant to the programs provided. Once the organization has decided to pursue COA accreditation, the accreditation agreement is signed and the work begins.

Intake

Think of the intake stage as COA’s opportunity to acquire information from the organization on all your programs and locations in which they operate. When highlighting the scope of services at each program, be concise. COA uses this information to determine the appropriate service standard for each program. Do not spend many months in this stage of the process – it will prolong the assignment of service standards. The organization’s Site Visit will not be scheduled until all program documentation has been submitted to COA.

Self-Study

When the organization enters the self-study stage of the accreditation process, all standard sections have been assigned and the due dates for the Preliminary Self-Study and Self-Study have been scheduled, along with the start date for the Site Visit.

During this phase of the accreditation process, the organization should implement the structure for managing the standards review. Work groups should conduct an assessment of its current practices, policies and procedures against the COA standards. A self-assessment helps the organization to know where it needs to prioritize its time and resources.

Site Visit

Once the Self-Study has been submitted, the accreditation work groups should begin compiling documentation to have available during the Site Visit. Reserve a meeting room for the Peer Review team to use while they are onsite for the duration of the Site Visit. All documentation should be clearly labelled by standard section, including the relevant core concept standard. The information the Peer Review team will evaluate can be available in paper or electronic format.

Building and sustaining momentum

If you are following the steps as listed, by now the “why” behind accreditation has already been established. An inventory of the strengths of staff has been conducted, and the process for managing the accreditation work is in place. Now the organization needs to formally roll out this significant initiative and keep staff engaged throughout the entire process.

Set a kick-off date

A kick-off event, such as an all-staff meeting, is a great way to launch the accreditation work. Use this time as an opportunity for the executive director to explain to staff why the organization is pursuing accreditation and why it is valuable. It is an opportunity to inform staff that pursuing accreditation can provide professional development and team building.

Themes and activities

Knowing the “why” behind the organization’s pursuit of accreditation may not be enough for some. For those who are charged with managing the accreditation process, consider ways to make different aspects of the work fun and exciting. Television shows, sports, movies, are all options that may be suitable to connect accreditation work groups. Visual display boards serve as a reminder and can foster healthy competition within the organization.

Final thoughts

The accreditation process can be overwhelming —there are many aspects that need to be managed. Hopefully, your creative juices are flowing with ways to make this organization-wide initiative manageable and fun. Remember, to get others involved, align the work with the strengths of staff and challenge the organization to always strive to be better.

Been through the accreditation process before? Share your thoughts on some things you wish you had known before you started the accreditation process. Recently completed the accreditation process? Let us know some of your pro tips that helped your organization through!

Active military and Veterans play an integral role in our everyday lives. Although we can’t always witness them in action or grasp the full breadth of their influence, we have confidence in their bravery and the safety they provide to our society on a daily basis. While we have this understanding, we also recognize that Veterans in this country often need support when they return home. Not only because of the inherent trauma of combat, but also because of the challenging economic situations that they often find themselves and their families in. We must continue to strive to do better by our Veterans. An example of progress in this area is the Supportive Services for Veteran Families (SSVF) program. This program addresses the varying needs of an individual Veteran and their family, by providing assistance with housing, transportation, child care, and the financial barriers that they may face.

SSVF was established in 2011 as a Rapid Rehousing and Homeless Prevention program to support homeless Veterans and their families in finding permanent housing and prevent homelessness for those at imminent risk due to the housing crisis at the time. In 2019, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is making $326 million in grants available to providers through a competitive application process, in order to assist them with providing SSVF services. These services assist Veteran families with outreach, case management, and assistance accessing and coordinating other services that promote housing stability and community integration. The program has had several successes since its inception.

In 2015, Virginia Governor Terry McAuliffe announced that Virginia would be the first state in the nation to functionally eliminate Veteran homelessness. The philosophy underlying the state’s initiative is housing first — a policy that holds that providing homeless people with safe, supportive housing is a precondition for attending to the issues that caused them to slip through the cracks in the first place. Supportive services in permanent housing typically keep residents linked to social workers and include health services — many single homeless adults have some kind of serious physical, mental or substance abuse-related problem — and job readiness programs .

Virginia is not the only state that has seen successes with this population. SSVF, Phoenix, Arizona was the first community in the country to end homelessness among veterans with lengthy histories of homelessness. The tenet of the program as described by one veteran, “I’m coming up on nine months sober, and a big part of it is because I have a roof over my head.” The program allows participants to prioritize their recovery because they are no longer consumed with the fundamental human need of finding shelter.

Many capacities/elements are considered when applying to be a SSVF provider, one of which is a provider’s accreditation status. The Council on Accreditation is recognized by the VA as an approved accreditor of SSVF services. SSVF providers that are COA accredited are eligible to receive a three-year funding award from the VA, while non-accredited providers are limited to one-year funding awards. Recognition of specific accreditors is often used as a tool for oversight entities, in this case the VA, uses accreditation to meet/or exceed oversight requirements. The VA also allows SSVF providers to use their funding to pay for accreditation. This incentivizes providers to become accredited and allows the VA to verify that these providers have gone through a rigorous third party review by an accreditor. Essentially the VA uses accreditation as a tool to indicate a quality provider with quality services, services that are best equipped to support U.S Veterans and their families.

Jill Albanese, Supervisory Regional Coordinator at the VA, oversees providers of the SSVF program and has been with the department since the creation of the program. Jill graciously took time to explain how the VA’s recognition of COA accreditation played a role in them determining funding for these grantees. Check out our discussion below.

COA: What was the genesis of recognizing an accreditor for this funding?

JA: When SSVF was being created we wanted to find a way to monitor and oversee the program consistently within our limited resources. We looked into how other non-profit oversight entities were doing this work and began learning more about the accreditation process.

COA: Why is accreditation status a component of the SSVF grant?

JA: We wanted agencies to become accredited, however we did not want to mandate it and limit services in a community if a provider does not yet have an accreditation status. To further incentivize accreditation we allow providers to use SSVF funds to pay for accreditation and allow accredited organizations to be eligible for three-year funding awards.

COA: Were those incentives effective?

JA: Yes, I would estimate that about half of all SSVF providers are accredited.

COA: How has recognizing COA accreditation impacted the VA’s oversight of the SSVF program?

JA: We’ve seen increased consistency amongst accredited SSVF providers. In addition, we have consistent oversight practices for accredited organizations that allows us to reduce the duplicative work that we do to monitor the programs. We use an Accreditation Tool that shows our auditors which review steps would have been covered for them to achieve accreditation. We can spend less time monitoring those sections already reviewed under the accreditation process and more time focusing on offering technical assistance to our providers. It saves time for auditors and providers.

COA: Can you tell us about the roll out of the accreditation provision?

JA: Initially, we gave priority funding to applicants that were already accredited at the time. Then we worked with each accreditor recognized to determine specific service sections that we felt most appropriately fit the SSVF program. The accreditors then crosswalked their standards with our regulations and we were able to achieve further consistency between provider agencies.

COA: What have you heard from providers related to the accreditation process?

JA: I recently spoke with a provider about this, they described the process as totally worth it. In fact, this particular provider is excited to now be mentoring another agency through the accreditation process. I’ve also heard positive comments on the standards themselves. The process is rigorous, particularly before the Site Visit, but overall providers seem to appreciate the organizational change it creates.

COA: How do you think the accreditation process has impacted SSVF providers?

JA: Anecdotally, there seems to be an increased sense of organization about them. Particularly in day-to-day work we’ve seen providers transform their processes and procedures, which has an improved impact on the services delivered. It has increased the expectation of quality amongst SSVF providers, which has led to increased quality amongst the providers applying for SSVF funds.

COA: As the oversight entity, have there been any challenges to having an accreditation component for the grant?

JA: SSVF is a dynamic program that is constantly changing. Our mission is always the same, but the method changes, in some instances these changes can be rapid. It helps that the accreditors are ready and willing to make changes when that happens.

COA: Are there any components of accreditation that you find particularly valuable as an oversight entity?

JA: The individual governance standards, and policies and procedures are extremely helpful. It provides agencies guidance and structure. If a provider loses a staff member having these components of accreditation in place help them stabilize, which is good for Veterans.

COA: What impact do you feel the accreditation process has on the individuals served by SSVF programs?

JA: Ultimately, the individual Veteran has been able to expect a greater emphasis on consistent services. Anecdotally, the providers seem to run smoother operations.

COA: Has the role of an accreditor created any efficiencies for the VA as an oversight entity?

JA: Program review has become more efficient. Grantees are more organized for the process, which allows us to save time on things that usually require a lot of back and forth. It saves a lot of time day-to-day.

COA: Is there anything else you want to share that we haven’t covered in these questions?

JA: It’s amazing to see the differences from one year to the next with these providers. They’re eager to share their progress and the successes their clients have achieved.

Thank you!

We would like to take a moment to thank Jill for her time and insights, but mostly for the work she does every day to support Veterans in this country. COA looks forward to our continued collaborative partnership with the VA.

We are all impacted by government spending and regulations beyond our day-to-day work in human services. Regulations empower us as consumers to make informed decisions about our health and safety. They give us peace of mind as employees, that our employer’s practices will be fair and that public spaces will be clean and meet the necessary standards.

We put faith in our political representatives to advance regulation in order to improve the overall welfare of our society. Over time we observe reactive regulation created to address urgent events, gradual regulation to help move the needle on key issues across a country, and preemptive regulation intended to aid the success of future generations.

Let’s explore the role of government regulations and learn more about their value to human services:

Need drives change

First, let’s discuss a historic example of the need for regulation. In September 1982, 12 year-old Mary Kellerman of Elk Grove Village, Illinois, died after consuming a capsule of extra-strength Tylenol. Within a month six more people in the vicinity would be dead and over 100 million dollars’ worth of Tylenol would be recalled from shelves across the United States. These instances amounted to what would be known as the Chicago Tylenol Murders.

The still unidentified perpetrator was purchasing Tylenol in the Chicago area, adding cyanide to the capsules, and returning them to the store. In turn the store was restocking shelves with the returned product and those that purchased and ingested the Tylenol died within an hour of consumption. Johnson & Johnson, maker of Tylenol, distributed warnings to hospitals and distributors and halted Tylenol production and advertising. Police drove through the streets of Chicago using megaphones to warn residents about the use of Tylenol.

In 1983, in response to the incident, Congress passed the Federal Anti-Tampering Bill, also known as the “Tylenol Bill”. The bill made it a federal offense to maliciously cause or attempt to cause injury or death to any person, or injury to any business’ reputation, by adulterating a food, drug, cosmetic, hazardous substance or other product. It also created a FDA requirement that all medications be sold in packaging with tamper-resistant technology.

In the face of a terrifying public safety situation, urgent government regulation was able to ease fears and create a foundation for the way medication is regulated in the U.S. today.

Regulation and our families

An example of regulatory oversight within the human services field is the passage of the Family First Prevention Services Act (FFPSA) by the U.S. Congress in 2018. It marks the largest reform of child welfare financing that has occurred in the past decade. The goal of the child welfare system is to keep all children and youth safe. The regulatory and spending path to deliver that safety has forever been changed because of this legislation.

Today it would be rare to find a human services professional that does not feel the primary initial goal for child placement is reunification with a parent or family member. Acknowledging that to keep kids safe in the long-term we must support families and alleviate issues that may lead to unsafe conditions/removal is widely accepted as best practice. The passage of FFPSA codifies this practice into law and allows funds to be used for family strengthening/preventative practices in child welfare agencies. This is a shift from exclusively funding out-of-home placement, which somewhat incentivized and eased this type of placement.

Though the enactment of FFPSA is a giant leap forward for the field, requiring some states and agencies to change decades of practices and redefining the way we regulate and implement a government program, the overall goal remains the same: to keep all children and youth safe.

Accreditation, a piece of the regulatory puzzle

Accreditation standards serve as a vehicle to implement and verify best practices. COA accreditation is recognized in over 300 instances across the US and Canada as an indicator of quality. In some cases the journey towards accreditation is due to a mandate, which is when states require that certain types of organizations become accredited. Another motivation for seeking accreditation might be due to deemed status, which is when state licensing bodies allow service providers to provide proof of accreditation in lieu of undergoing certain parts of the licensing process. The practice of states/provinces recognizing accrediting bodies is one way that they implement regulation, oversee services, and work to increase quality of services. We recommend checking out the blog post, Help! I’m Mandated! Now What? Choosing an Accreditor to learn more about navigating this topic.