It is no secret that the Council on Accreditation (COA) believes in what we do. We promote best practices and help our organizations to implement them with the aim that clients across the social services field will get the best possible quality of care. By accrediting the entire organization, we ensure that everyone—from human resources to finances to support staff—is working together to carry out that mission.

This is the “why” of organizational accreditation for COA and our accreditees alike. We are all here to do good; following best practices helps us do good in the most effective way possible.

Improving service quality is the most important benefit of organizational accreditation. But from our experience, it is not the only benefit! Every time an organization completes the accreditation process, COA asks about its impact. Several themes have come out of our survey responses.

Organizational accreditation improves operations.

Whole-organization accreditation provides a framework for staff to look at how they fulfill their mission now and discover how they can do so better. The benefits along the way are multifold: more open communication, sound strategic plans, streamlined work systems, better risk management…the list goes on. When an organization looks at itself holistically, it can find the root of any problems and be better equipped to solve them.

94% of COA-accredited organizations agree that accreditation improves organizational learning and knowledge. 82% agree that it improves organizational capacity. COA accreditation has helped some organizations bring themselves back from the brink of bankruptcy; others have used it as a tool to position themselves to become leaders in the field.

Many have expressed that reaccreditation is not an end of itself, but a tool to help them achieve new heights of living their mission. COA is proud to help them do that.

Organizational accreditation boosts marketability.

Organizational accreditation is a professional, 3rd-party recognition that an organization meets the highest standard for both quality service delivery and administrative practices. The effort that an organization goes through to achieve accreditation proves just how much its staff cares about what they do.

This hard work helps organizations stand out among competitors and builds goodwill. 85% of our organizations agree that COA accreditation improves their organization’s marketability. 90% agree that it improves their relationship with external stakeholders. Clients and community alike are looking for signs of quality—accreditation gives them a big one.

Organizational accreditation helps secure funding.

Organizational accreditation verifies that an organization not only does quality work, but also has sound financial, administrative, operational, and oversight practices. This third-party verification can inspire the confidence funders need to support an organization as it continues to grow.

This can help in terms of government funding, as well. COA is recognized in over 300 instances in 50 U.S. states, the District of Columbia, Canada, and China. Our list of recognitions continues to grow, and with it the financial benefit to our accredited organizations. As of December 2018, 70% of our organizations agree that COA accreditation ensures funding.

Organizational accreditation can give staff a sense of fulfillment.

Accreditation encourages organizations to look at themselves frankly and work toward continuous quality improvement. This can allow staff to take a break from their daily grind and appreciate the big picture of their impact. Organizational accreditation also facilitates transparency and open communication, which can increase trust and the feeling that everyone is working as part of one team. Finally, the quest for quality improvement provides staff with new professional opportunities, allowing them to lead the charge toward a brighter future for those they serve.

Almost three quarters of COA-accredited organizations agree that accreditation improves workforce engagement, and over half agree that it improves staff retention. Many of our organizations describe how empowering it is to see the change in mindset that accreditation can bring.

Organizational accreditation holds the team to its goals.

As anyone with a broken New Year’s resolution knows, it is easy to put great plans in place and never carry them out. Accreditation (and reaccreditation!) forces organizations to follow through with those great plans, holding them accountable to be the best they can be.

94% of COA-accredited organizations agree that our whole-organization accreditation improves transparency and accountability. Through it, staff become not only accountable to their clients and stakeholders, but to themselves.

Time and time again, accreditation has proved transformative for our organizations, supporting their mission and allowing them to provide clients with the quality service they deserve. COA is grateful and humbled to be a part of this important process.

Have you experienced other accreditation benefits not listed here? Share them with us in the comments!

SOURCE: All statistics are pulled from 2018 survey data from organizations accredited by the Council on Accreditation (COA).

Active military and Veterans play an integral role in our everyday lives. Although we can’t always witness them in action or grasp the full breadth of their influence, we have confidence in their bravery and the safety they provide to our society on a daily basis. While we have this understanding, we also recognize that Veterans in this country often need support when they return home. Not only because of the inherent trauma of combat, but also because of the challenging economic situations that they often find themselves and their families in. We must continue to strive to do better by our Veterans. An example of progress in this area is the Supportive Services for Veteran Families (SSVF) program. This program addresses the varying needs of an individual Veteran and their family, by providing assistance with housing, transportation, child care, and the financial barriers that they may face.

SSVF was established in 2011 as a Rapid Rehousing and Homeless Prevention program to support homeless Veterans and their families in finding permanent housing and prevent homelessness for those at imminent risk due to the housing crisis at the time. In 2019, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is making $326 million in grants available to providers through a competitive application process, in order to assist them with providing SSVF services. These services assist Veteran families with outreach, case management, and assistance accessing and coordinating other services that promote housing stability and community integration. The program has had several successes since its inception.

In 2015, Virginia Governor Terry McAuliffe announced that Virginia would be the first state in the nation to functionally eliminate Veteran homelessness. The philosophy underlying the state’s initiative is housing first — a policy that holds that providing homeless people with safe, supportive housing is a precondition for attending to the issues that caused them to slip through the cracks in the first place. Supportive services in permanent housing typically keep residents linked to social workers and include health services — many single homeless adults have some kind of serious physical, mental or substance abuse-related problem — and job readiness programs .

Virginia is not the only state that has seen successes with this population. SSVF, Phoenix, Arizona was the first community in the country to end homelessness among veterans with lengthy histories of homelessness. The tenet of the program as described by one veteran, “I’m coming up on nine months sober, and a big part of it is because I have a roof over my head.” The program allows participants to prioritize their recovery because they are no longer consumed with the fundamental human need of finding shelter.

Many capacities/elements are considered when applying to be a SSVF provider, one of which is a provider’s accreditation status. The Council on Accreditation is recognized by the VA as an approved accreditor of SSVF services. SSVF providers that are COA accredited are eligible to receive a three-year funding award from the VA, while non-accredited providers are limited to one-year funding awards. Recognition of specific accreditors is often used as a tool for oversight entities, in this case the VA, uses accreditation to meet/or exceed oversight requirements. The VA also allows SSVF providers to use their funding to pay for accreditation. This incentivizes providers to become accredited and allows the VA to verify that these providers have gone through a rigorous third party review by an accreditor. Essentially the VA uses accreditation as a tool to indicate a quality provider with quality services, services that are best equipped to support U.S Veterans and their families.

Jill Albanese, Supervisory Regional Coordinator at the VA, oversees providers of the SSVF program and has been with the department since the creation of the program. Jill graciously took time to explain how the VA’s recognition of COA accreditation played a role in them determining funding for these grantees. Check out our discussion below.

COA: What was the genesis of recognizing an accreditor for this funding?

JA: When SSVF was being created we wanted to find a way to monitor and oversee the program consistently within our limited resources. We looked into how other non-profit oversight entities were doing this work and began learning more about the accreditation process.

COA: Why is accreditation status a component of the SSVF grant?

JA: We wanted agencies to become accredited, however we did not want to mandate it and limit services in a community if a provider does not yet have an accreditation status. To further incentivize accreditation we allow providers to use SSVF funds to pay for accreditation and allow accredited organizations to be eligible for three-year funding awards.

COA: Were those incentives effective?

JA: Yes, I would estimate that about half of all SSVF providers are accredited.

COA: How has recognizing COA accreditation impacted the VA’s oversight of the SSVF program?

JA: We’ve seen increased consistency amongst accredited SSVF providers. In addition, we have consistent oversight practices for accredited organizations that allows us to reduce the duplicative work that we do to monitor the programs. We use an Accreditation Tool that shows our auditors which review steps would have been covered for them to achieve accreditation. We can spend less time monitoring those sections already reviewed under the accreditation process and more time focusing on offering technical assistance to our providers. It saves time for auditors and providers.

COA: Can you tell us about the roll out of the accreditation provision?

JA: Initially, we gave priority funding to applicants that were already accredited at the time. Then we worked with each accreditor recognized to determine specific service sections that we felt most appropriately fit the SSVF program. The accreditors then crosswalked their standards with our regulations and we were able to achieve further consistency between provider agencies.

COA: What have you heard from providers related to the accreditation process?

JA: I recently spoke with a provider about this, they described the process as totally worth it. In fact, this particular provider is excited to now be mentoring another agency through the accreditation process. I’ve also heard positive comments on the standards themselves. The process is rigorous, particularly before the Site Visit, but overall providers seem to appreciate the organizational change it creates.

COA: How do you think the accreditation process has impacted SSVF providers?

JA: Anecdotally, there seems to be an increased sense of organization about them. Particularly in day-to-day work we’ve seen providers transform their processes and procedures, which has an improved impact on the services delivered. It has increased the expectation of quality amongst SSVF providers, which has led to increased quality amongst the providers applying for SSVF funds.

COA: As the oversight entity, have there been any challenges to having an accreditation component for the grant?

JA: SSVF is a dynamic program that is constantly changing. Our mission is always the same, but the method changes, in some instances these changes can be rapid. It helps that the accreditors are ready and willing to make changes when that happens.

COA: Are there any components of accreditation that you find particularly valuable as an oversight entity?

JA: The individual governance standards, and policies and procedures are extremely helpful. It provides agencies guidance and structure. If a provider loses a staff member having these components of accreditation in place help them stabilize, which is good for Veterans.

COA: What impact do you feel the accreditation process has on the individuals served by SSVF programs?

JA: Ultimately, the individual Veteran has been able to expect a greater emphasis on consistent services. Anecdotally, the providers seem to run smoother operations.

COA: Has the role of an accreditor created any efficiencies for the VA as an oversight entity?

JA: Program review has become more efficient. Grantees are more organized for the process, which allows us to save time on things that usually require a lot of back and forth. It saves a lot of time day-to-day.

COA: Is there anything else you want to share that we haven’t covered in these questions?

JA: It’s amazing to see the differences from one year to the next with these providers. They’re eager to share their progress and the successes their clients have achieved.

Thank you!

We would like to take a moment to thank Jill for her time and insights, but mostly for the work she does every day to support Veterans in this country. COA looks forward to our continued collaborative partnership with the VA.

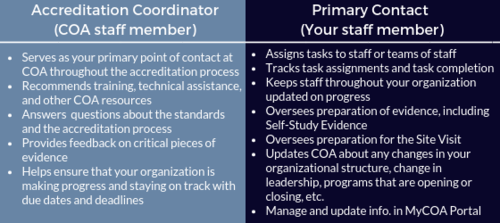

Accreditation is a journey. One with a clear destination, but a less defined path. There are mile markers along the way; however, there isn’t necessarily one straight, easy road to the finish line. Is there a recommended route? Are there any anticipated hurdles? If you are tasked with leading the accreditation process for your organization, you may not know where to start. This is where COA’s Accreditation Coordinators come in.

Every organization seeking COA accreditation is assigned an Accreditation Coordinator, a COA staff member that serves as a single point-of-contact throughout the accreditation journey. The role of the Accreditation Coordinator is unique to COA’s facilitative accreditation process. They work closely with the organization’s designated single point-of-contact, which COA refers to as the Primary Contact. Through this partnership, an organization obtains the support they need to navigate the road ahead.

Roles and responsibilities

Accreditation Coordinator

An Accreditation Coordinator works concurrently with a number of organizations. Their caseload can vary as well as the needs of each organization. The coordinators can also specialize in distinct accreditation programs or service types (Financial Education and Counseling, Employee Assistance Programs, Opioid Treatment Providers, etc.). Communication is a key element to this role. They’re responsible for answering questions, providing feedback on submitted documentation, and referring organizations to training and resources. Whether it’s to discuss specific documentation, standards, practices, or policies, they’re available on a daily basis to address inquiries from organizations. And because each organization comes with unique questions and circumstances, researching program models and administrative practices is also part of the work.

While the day-to-day routine of an Accreditation Coordinator involves providing tailored support to organizations, it is also valuable to note the role’s limitations. Accreditation Coordinators are not consultants and do not provide consultation to organizations. They can help Primary Contacts interpret the standards and answer questions, but are unable to dictate how implementation will look on the ground. Organizations are responsible for the application of the standards. And while they review and provide feedback on select pieces of evidence, specifically six key documents referred to as the Preliminary Self-Study (PSS), it is not within their role to review the entire Self-Study (aka all of the evidence that is required based on the assigned standards). The Site Review Team assesses the Self-Study prior to the Site Visit and will provide the ratings after conducting the on-site review.

Primary Contact

The Primary Contact is COA’s champion at the organization level and is in charge of spearheading the accreditation process. In this role, they’re responsible for engaging organization staff in all things COA. While the Primary Contact is the single point-of-contact, accreditation is by no means a one-person job. Accreditation is a huge team effort, from pulling together Self-Study evidence to preparing for the Site Visit, and the Primary Contact is the team captain. It’s no coincidence that we have repeatedly heard the role compared to “herding cats”!

Exploring the relationship between the Accreditation Coordinator and the Primary Contact

COA’s mission is to partner with human service organizations worldwide to improve service delivery outcomes by developing, applying, and promoting accreditation standards. The relationship between the Accreditation Coordinator and the Primary Contact brings that partnership to life. The two work together throughout the accreditation process, from start (the intake call) to finish (the notification of accreditation). They’re there to kick off the expedition, advise you of the twists and turns, help navigate roadblocks, and ultimately make sure your organization hits all the necessary milestones en route to the final destination. Along the way, Primary Contacts should provide the Accreditation Coordinator with updates on their progress, highlighting successes and challenges. That information helps COA gauge the organization’s strengths and needs and informs the provision of targeted supports.

Learning about the challenges of navigating the process is vital to COA. We want to know about the unexpected obstacles in order to assist with readjusting your approach and preventing you from spiraling off course. For example, Performance and Quality Improvement (PQI) can be one major hurdle for organizations. As the Primary Contact it can feel daunting to try to implement a culture of PQI, especially if your organization doesn’t have the framework in place. As an Accreditation Coordinator, some of my favorite moments working with Primary Contacts have come from discussing the evolution of PQI. It could be talking through the development of a PQI committee (“Who should be on it?” “How often should they meet?”) or figuring out performance and outcome measures (“Can you explain outputs and outcomes again?” “What are some examples of operations and management performance measures?”). Standards and technical assistance inevitability guide the conversation, but it’s through this exchange that we learn how an organization goes about creating change. And isn’t that what it’s really all about? PQI helps an organization become stronger to better serve their clients and community.

The relationship between the Accreditation Coordinator and Primary Contact is not one-size-fits-all. We are there to support in whatever capacity is most beneficial for the organization. For some this may take the form of structured monthly check-in calls, while others prefer Q&A exchanges over email. We recommend that organizations new to the accreditation process or new to the role of Primary Contact have more regular communication with their Accreditation Coordinator. Seasoned individuals may not need to rely on their coordinator as much; they remember the journey and have their path mapped out. Regardless of the frequency of contact, the door for communication is always open.

Tips for Primary Contacts

We know that serving as the Primary Contact is not an easy task. Often the work of accreditation is piled onto an already full plate. Here are some tips and tricks from COA’s team of Accreditation Coordinators:

- Use your Accreditation Coordinator as a resource. If you feel stumped or confused, don’t hesitate to reach out to your Accreditation Coordinator. Ask questions, it is what we are here for! That said, sometimes we get such excellent (and complex) questions that we need to consult with the team or the Standards Development department, which requires additional time. So it may take us time to get back to you with a response, but don’t worry; we will get back to you as soon as possible.

- Send us an email or schedule a call. The Accreditation Coordinator’s daily responsibilities are often collaborative – meeting frequently with organizations, our team, and other COA colleagues – which can sometimes impact our availability. We know Primary Contacts have busy schedules too. No one enjoys playing phone tag, it is best to schedule a call or send us an email. Our typical response time is 24 to 48 hours.

- Become friends with the MyCOA portal. We recommend that all Primary Contacts (and staff working actively on the process) participate in one of the regularly scheduled Intake Webinars in order to review all of the portal’s features and functionality. We don’t want to brag, but it is pretty cool! We encourage you to get familiar with the portal since this is where you will be completing the majority of the work. Check out the Step Pages, search for tools, and click all the buttons! Well not all the buttons.

- Attend a COA face-to-face training. There is no better way to familiarize yourself with all aspects of COA than attending either the in-person 2-day Intensive Accreditation Training or 1-day Performance and Quality Improvement Training. These in-person trainings provide Primary Contacts with an opportunity to learn from COA subject matter experts, meet COA staff and network with other organizations. We recognize this might not be a feasible option for all organizations due to limited resources and capacity. Therefore, we also offer a variety of complimentary live webinars and self-paced trainings covering similar curriculum. You can learn more and register through the Training Calendar.

- Don’t panic! This might be the most important tip on this entire list! The accreditation process is meant to be rigorous, but achievable. The goal is that you end the journey stronger than when you started. Change doesn’t happen overnight and it isn’t always easy, however, it is possible. The best advice for Primary Contacts is to not get overwhelmed; take the process one step at a time. Creating a work plan and communicating expectations to your team (don’t forget to enlist their help) is a good place to start. Have fun with it too! We have seen many primary contacts tap into their creative sides to invent games or enjoyable activities to get their team on board the COA train.

Training and resources

Want to know how to create a policy? We have a tip sheet for that! Want to know how to develop a strategic plan? We have a template (along with a self-paced training and blog post) for that! We’ve included just a few of the many resources that can help organizations on the road to achieving COA accreditation. We recommend exploring the full breadth of resources by accessing the tool search in the MyCOA Portal.

- Accreditation Learning Plan

- Getting Organized: Creating an Accreditation Workplan

- Preliminary Self-Study Fact Sheet

- Three-Part PQI Recorded Webinar Series

- PQI Tool Kit

- Preparing for the Site Visit

You are not alone

Many of us at COA have a social work (or social work adjacent) background, and the work we do to support Primary Contacts in their efforts to create change in their organizations, mirrors the work organizations do with their clients. We conduct an assessment. We create a service plan. We deliver supports and linkages to necessary resources. The makeup of our caseloads may be different, but we are all working towards a common goal – positive client outcomes and high quality services.

And as you learn from us, we learn from you. You are the change makers, advocating for those that you serve and making an impact on your communities. For many of us, the stories that you share and the work that you do are why we walk through the doors at COA. You are our direct connection to the field. Our collaboration allows us to gain a better understanding of service delivery and program models, as well as how the implementation of best practice looks on the ground for organizations of all shapes and sizes.

At the end of the day, an organization is ultimately responsible for their accreditation process, however, you are not alone on the journey. COA’s Accreditation Coordinators are there to support you and your team.

When the Family First Prevention Services Act (H.R.253) was passed, it recognized that the best placement for children is in the least restrictive setting. This is also true for undocumented children in the custody of the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR).

In that regard, since 1997, the Flores Settlement Agreement has defined the rights of these children. In essence, it obligates the government to keep the children in the least restrictive setting and sets standards for their care. Recently, however, the Departments of Homeland Security (DHS) and Health and Human Services (HHS) have put forth a proposal to withdraw the agreement.

The agreement was never meant to be a de facto law so much as a framework, and in the original agreement there was a sunset clause expiring the agreement after 5 years provided the government implemented the terms of the settlement as federal regulation or Congress superseded it. Neither has happened. In fact, in 2015 the settlement was expanded to include all minors who come across the border without legal authorization (not just the unaccompanied ones who become custody of the federal government).

Despite the absence of the required federal regulation or congressional action, DHS and HHS have begun the process to withdraw the agreement. In doing so, families could be detained and placed in less regulated facilities, broadening the allowances for emergency loopholes for not meeting standards of care, and making it easier for government to revoke legal protections for unaccompanied minors.

This proposed rule change includes a comment period that ends November 6th, 2018 after which Judge Dolly Gee will determine whether the regulations are eligible to supersede the Flores Settlement Agreement. COA is urging interested parties to provide comments which put forth recommendations that emphasize the well-being of a child, and which ensure that migrant children receive trauma-informed and evidence-based care in the least restrictive setting.

The best practice of care for these children was established by the Flores Settlement Agreement and is contained in COA’s UC standards. It includes wraparound services to support their integration into society and placing them with kin or resource families in the most home-like settings. It has been two decades since the Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) Study was conducted and the lessons learned have been indelible to the field: childhood trauma has long lasting effects. We cannot discuss the needs of this population without discussing the need for trauma-informed care.

So what can we do as human service professionals? Well, there are a few options:

- COA has put forth standards we consider best care for unaccompanied children. These standards are available our website. All comments and feedback will help shape the voice we provide DHS and HHS.

- Share your comments about what is best for children. Go to the Regulations.gov website for instructions on how to comment. Need some help with this? Here’s a resource to help you craft your response.

- Reach out to your representatives and ask what their plan is for the comment period and how they are defining proper care for unaccompanied minor children.

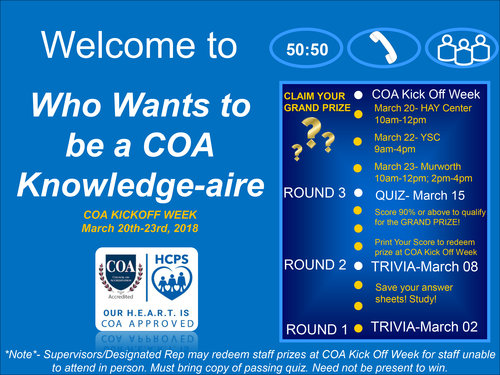

The accreditation process is most valuable when staff throughout the agency are engaged, but this isn’t always easy. Harris County Protective Services for Children and Adults shares the fun, interactive methods they used to promote the culture of COA and gain staff buy-in.

The phrase “THEY ARE COMING” typically strikes fear in the hearts of agency staff and leadership preparing for a reaccreditation Site Visit. Even scarier is that a lot of the staff not directly involved in the process never know exactly who “THEY” are.

Since the last Site Visit 4 years ago, our organization had experienced many changes to leadership. Our Quality Improvement Team had transitions in roles and was now staffed with a diverse team with a fresh set of eyes for COA.

As a team new to the process, one of the first things we did was an assessment of staff feelings and knowledge about COA.

Challenge #1: Even though our organization has been successfully reaccredited since 1978, staff still remained in panic mode.

When it was time for our formal Site Visit COA continued to be viewed as a separate entity, a “THEY” of sorts. We wanted to be sure that the view was of our partner helping us to identify strengths and areas for improvement in ways that may not be immediately apparent. We realized that part of the issue was that historically, we had not engaged and educated ALL staff (and not just those involved in turning in evidence). We needed to reframe staff perceptions as COA being a positive experience and focus on the benefits of the visit instead of just focusing on meeting deadlines to turn in evidence.

Challenge #2: What did we do to engage staff before? What resources do we have to engage over 19 different programs with field and on site staff?

We convened a think tank of new and seasoned staff from Quality Improvement, Communications and our Training Institute. At the last Site Visit we were only able to reach staff via email blasts and a creative “Go for the Green COA Poem.” Though staff comments about COA from past surveys and focus groups was reviewed, it was hard to track who actually opened the emails and who really took-home the message of what COA is all about.

We wanted to do something different and FUN that would appeal to our two majority generations in the agency identified from our annual staff survey: millennials and baby boomers.

Out of our think tank was born the theme for our COA Kick Off Week online Challenge, “Who Wants To Be A COA-Knowledgaire”, which included a teaser video about COA starring our own “COA Queen” which addressed and made light of staff feelings about COA.

Teaser Video

We also found online templates for interactive Power Point Shows that were clickable to reveal correct (or incorrect, buzz!) answers that staff could complete each week to gain knowledge instead of having to read long text.

If staff passed the Grand Challenge Quiz (via Survey Monkey) with 90 or above, they were eligible to redeem limited edition swag items. The swag items, though a small investment from the Quality Improvement department ($2,000), made for an effective incentive that got many unfamiliar faces involved and increased word of mouth.

At the end of the challenge, almost 50% of our staff had participated visiting us in person at each site to collect their unique swag, a huge participation success for a governmental agency.

The Quality Improvement Team showing off their COA swag.

We have additional engagement activities planned for the months leading up to our visit to keep the momentum going and to continue promoting our Site Visit as an opportunity to showcase our programs and to learn about the up and coming best practices for social service agencies and nonprofits. To learn more about HCPS on their website and Facebook.

Resources

- Flip card Trivia

- How to make a power point show auto-run and clickable

- WHO WANTS TO BE A MILLIONAIRE GAME TEMPLATE sample template by Mark Damon

The views, information and opinions expressed herein are those of the author; they do not necessarily reflect those of the Council on Accreditation (COA). COA invites guest authors to contribute to the COA blog due to COA’s confidence in their knowledge on the subject matter and their expertise in their chosen field.

Emmony Pena

Emmony is a Licensed Master Social Worker from the University Of Houston Graduate College Of Social Work with a focus on program development and evaluation. She has 5 years of experience in Data Analysis and Process Improvement through her graduate research assistant experience at MD Anderson and in her current role as Quality Improvement Professional at Harris County Protective Services. Emmony’s goal is to engage staff in performance and quality improvement activities and in plan-do-study-check act cycles.

Emmony monitors the implementation of the agency’s Performance and Quality Improvement plan and provides technical assistance and leadership to programs in the areas of Council on Accreditation standards, data collection, logic model development, focus groups, case review audits and trainings.

Certifications: CANS Assessment (Child and Adolescent Needs and Strengths) Certified

A big thank you to Stan Capela of Heartshare Human Services of New York for this guest post!

My name is Stan Capela and I have been a COA Peer Reviewer and Team Leader since 1996. By the end of April, I will have completed 112 Site Visits. At the glorious age of 65 after devoting 40 years to the field of social services, I’m beginning to reflect back on my journey. I want to share my experiences with you in honor of Volunteer Month.

Before I share my story let me give you a snapshot of a Volunteers numerous responsibilities. First you are assigned a Site Visit. I started as a Peer Reviewer, working with a team of colleagues to review an organization. Ten years ago, I became a Team Leader and gained more responsibilities such as; making contact with the organization, setting up travel for the Peer Review team, developing the Site Visit schedule, assigning standards sections to the Peer Reviewers, and leading the entrance and exit meetings where the team interacts with the organization. The latter gives the Peer Review team a chance to introduce themselves to the organization and provide information about how the review will take place.

Wait! I’m getting ahead of myself. The entire review process begins with a Self-Study submitted by the organization and reviewed prior to their Site Visit. When the review team arrives on-site most of their time is spent reviewing case records, policies and conducting interviews. By the time the exit meeting occurs, the Team Leader and review team are ready to provide an overview of the organization’s strengths and challenges. If you want to learn more about the Site Visit process then I recommend reading Recipe for Conducting Quality Accreditation Site Visits which I co-authored with Joe Frisino, a member of the COA Standards Development team, in New Directions for Evaluation.

The decision to become a COA Volunteer starts with the simple question, why? And traveling through my many memories leads me to that answer.

I remember on my first Site Visit I was eating dinner and mistakenly bit into an olive and broke my tooth. The executive director of the organization we were reviewing offered to have one of her board members who was also a dentist patch me up. I declined since I felt it would be a conflict of interest. After all it was just a cracked tooth.

Another significant memory is when I interviewed two girls, one 8 years old and the other 12 years old. They both had been abused and while talking with them they expressed how much they appreciated the staff helping them get through their pain.

There was also a memorable exit meeting where I remember commenting on the risk management minutes and asking who was responsible for creating them. A woman stood up and I complimented her on her work. That moment made the executive director stand up in that same meeting and say, “it goes to show you, we are all a part of a team dedicated to helping people in their time of need.” At the conclusion of that exit meeting the employee I engaged with beamed with pride as leadership walked over to say that they didn’t realize they were in the presence of such a star.

Once I was making the rounds and asked an employee to tell me a story that would make me remember the organization. He told me about Johnny and the mailbox. Basically, it was an individual with developmental disabilities who lived in a group home. One of his goals was to get the mail and distribute it. One day he went outside to the mailbox and found a baby inside. Johnny being trained properly brought the baby inside and gave it to the site manager. Many years later there was a knock on the door. The site manager opened the door and saw a very professional looking woman who asked for Johnny. The site manager said Johnny passed away a few years ago. The woman said I was the baby and wanted to thank him.

I remember another time that I was scheduled to meet with a client during a Site Visit. The client was transgender. During the interview the client expressed appreciation for how the staff treated her while she was transitioning. It felt good to hear how well the staff supported her and addressed her needs.

I have many more stories but these are just a few. So again, why? It’s about interacting with people and observing inspiring team work. When I conduct an entrance meeting as a Team Leader, I start by saying I know this is a lot of work, but we’ll get through it together. You should look at this Site Visit as an opportunity to invite people into your home and share your world with them. I try to get the point across that we are a family of helpers who have dedicated our lives to helping people in need and going through the accreditation process provides an opportunity to affirm what we do.

It’s very easy for me to answer the question why become a COA Volunteer after all these experience in these roles. My time as a Volunteer has made me feel like the richest person on the face of this earth. Again, why? Simple, I have decided to help people in my work at HeartShare Human Services of New York and in these roles at COA. In all my roles I’m able to make sure we all strive to meet the highest standards to reaffirm that the work we do meets the needs of the people we serve.

The views, information and opinions expressed herein are those of the author; they do not necessarily reflect those of the Council on Accreditation (COA). COA invites guest authors to contribute to the COA blog due to COA’s confidence in their knowledge on the subject matter and their expertise in their chosen field.

Stan Capela

Stan Capela spent 40 years in the field of program evaluation working the first ten at Catholic Charities for the Diocese of Brooklyn and Queens and the last 30 at HeartShare Human Services of New York formally known as Catholic Guardian Society of Brooklyn and Queens. During his time there he has had the opportunity to do a wide range of program evaluation, staff development workshops and presentations at various conferences such as American Evaluation Association, Canadian Evaluation Society, American Sociological Association, and Society for Applied Sociology to name a few. In addition, he participated on a variety of committees that played a role in developing a competency based child welfare training program known as the New York City Training Consortium. The program is overseen by the Council of Family and Child Caring Agencies. Finally, Stan participated on an internal committee at his current organization that developed a management training program that was the recipient of the COA Innovative Practice Award in 2012.

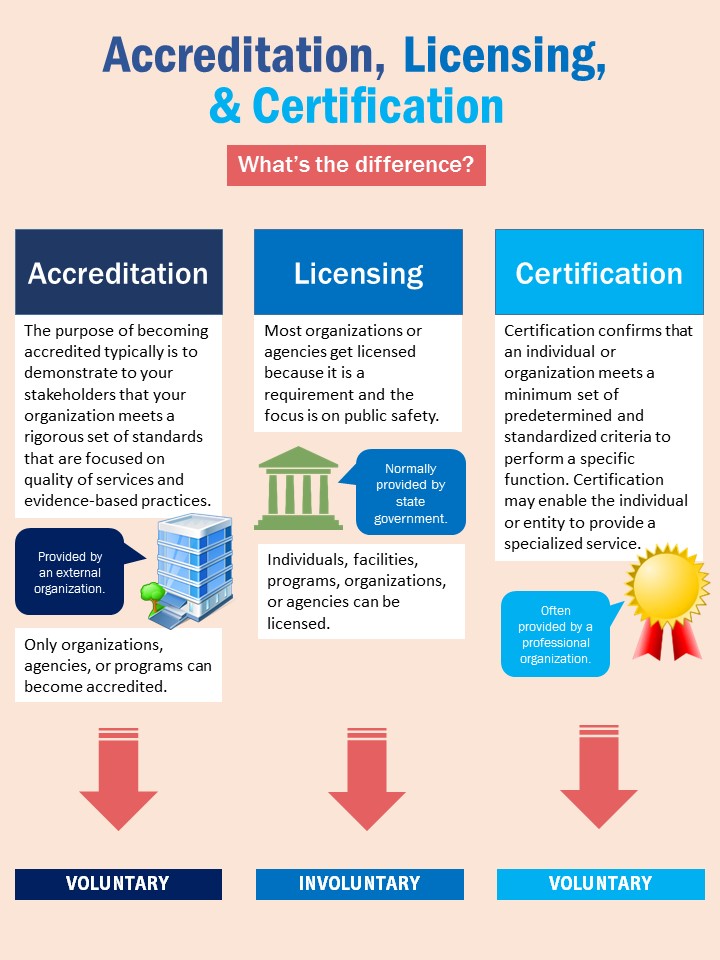

One of the most frequently asked questions we get from organizations, is what the differences are between these three entities: accrediting bodies, licensing authorities, and certification organizations. Commonly there is overlap, but sometimes there are distinct differences. Before we explore those differences, there are a few points to highlight:

- Accreditation, licensing, and certification may vary by location and by the entity providing the credential. While we hope this article is helpful in providing a basic understanding, always be sure to check with your local jurisdiction to determine what is required.

- There is often an interdependence between these three categories. We discuss this correlation later in the post.

- Accreditation, licensing, and certification are not interchangeable terms. They each have a unique meaning and implication.

Now let’s walk through the definitions and examples of each category, and then take a look at some examples of how they can overlap. There’s an infographic at the end of the post that gives an overview of this discussion.

Accreditation

- Accreditation is both a process and a credential

- The accreditation process is voluntary

- Only organizations, agencies, or programs can be accredited

If an organization is accredited this means they conducted a thorough self-assessment and compared themselves to recognized standards of best practice. Accreditation means that the organization, agency, or program was able to demonstrate evidence of implementation to all of the relevant standards. It is a rigorous process conducted by a third party organization.

The process is voluntary; however regulating bodies often require accreditation in order to be licensed or certified. The accreditation process typically repeats every 2-4 years, depending on the accrediting body. Normally, individuals or private practices are not able to become accredited; however, some exceptions may exist.

Example:

The Council on Accreditation (COA) develops standards and guidelines for the accreditation of services delivered by behavioral health and social service agencies. The accreditation process is designed to assist agencies in implementing organizational structures (i.e. financial management), and processes of care (i.e. case-management) that will help them achieve better results in all areas, and ultimately improve the well-being of their clients. Organizations use their accredited status to demonstrate accountability to clients, funders and donors.

Accreditors of human and social services

The most common accreditors of human and social services are as follows:

Council on Accreditation (COA)

CARF

Joint Commission

Here’s a comparison between the above accrediting bodies.

Licensing

- Licensing exists primarily for public safety and the well-being of consumers

- Typically, licensing is involuntary

- Individuals, facilities, programs, organizations or agencies can be licensed

Individuals are often licensed by their respective state to practice counseling, social work, or nursing. Organizations may need to be licensed in order to provide a specific service such as services for substance use disorders or residential treatment. Practitioners and programs are required to be licensed or face penalties, including suspension or closing of agency.

Examples:

Under New York State law, no organization may operate an adult group home without a license.

In most states, including New York, individual social workers must have a clinical license in order to provide psychotherapy without supervision.

Certification

- Certification demonstrates the capability to provide a specialized service or particular program

- Typically, certification is voluntary, but sometimes regulatory bodies require certification in order to provide a specific service

- Individuals, facilities, programs, organizations or agencies can obtain certification

Certifications at the organizational level can definitely vary, including the terminology. Some structured evidence-based models require certification. In these cases, the certification can be called “authorized provider” or “approved site.”

Example:

We also often see certifications for individuals. Many schools of social work have certificate programs. For example, Tulane University in New Orleans, Louisiana offers a certificate in Family Practice. This is an opportunity for students to get a specialized education and accrue experience in this specialized area which they can include on their resumes.

Understanding the correlation between accreditation, licensing and certification

More and more, regulating bodies are requiring that organizations become accredited or certified in order to be a licensed provider in their respective state.

Examples:

Effective January 1, 2017 in California foster care providers must be accredited or in the process of being accredited to qualify as a licensed provider. We call this a recognition, the state is recognizing the value of accreditation and using it to identify credible and accountable organizations who have implemented best practices.

In Nebraska, organizations must be certified in Functional Family Therapy (FFT LLC) to be a licensed provider. In this example, the state is relying on a certification to ensure that specific models are implemented and relying on FFT LLC to track the fidelity of the program model.

Final takeaways

- Always pay attention when you see the words “license,” “certification,” and “accreditation.” Whether you are applying for a grant or soliciting funds from a donor, be sure to use the appropriate terms and understand what the entity is requesting.

- Don’t be afraid to ask about what the terms mean. With so many different regulating bodies out there, you want to be sure that you are all on the same page.

- Never make false claims about your credentials; you will always need documentation to support your status. Not that organizations would intentionally make a false claim, but accidentally using the wrong terminology can lead to problems.

- Stay on top of the changes and requirements of your regulating or accrediting bodies. This can be a challenge in our ever-evolving field. When there’s transition, licensing, certifying, and accrediting bodies must adjust as well. A great way to bolster your risk prevention activities is to have an internal process that regularly reviews changes in requirements. Subscribe to COA’s newsletter for standards updates.

We hope you now have a better understanding of these terms, or at least with recognizing when you need to ask more questions to ensure that your organization remains in good standing with all entities that have a stake.

Here’s an infographic summarizing what we went over in this post, feel free to share it!

Community demographics are continuing to evolve nationwide, making the need for culturally competent organizations more prevalent than ever. In this article, we will discuss what this means for you as a provider of social services, and how your organization can progress in this realm by exploring the what, why and how of cultural competence.

The what

First, let’s define cultural competence. It can loosely be defined as the ability to respect, engage, and understand individuals who have different cultural or belief systems, where the elements of culture include, but are not limited to: age, ethnicity, gender identity, gender expression, geographic location, language, political status, race, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, tribal affiliation, and religion.

The why

The term competency in regards to culturally responsive practice has been debated. Can one ever truly be culturally competent? There might not be a consensus, but as a provider of social services promoting cultural competence will enable you to better meet the needs of the individuals, children, and families you serve. Understanding your community and those you serve facilitates stronger partnerships, resulting in higher quality programs and service delivery. Research shows that organizational culture impacts its effectiveness. An organization that commits to cultural competence is not only better equipped to successfully address community service gaps and needs, but also creates an internal culture that fosters responsive and respectful interactions.

Here are just a few of the many benefits, it:

- fosters stakeholder engagement and empowerment

- ensures strategic initiatives, goals, and objectives to be culturally appropriate and inclusive of community needs

- supports the recruitment and retention of a diverse and inclusive governing body and workforce

- creates a safe and supportive environment that accepts and respects diversity

The how

Seek stakeholder feedback

Connect with your community! The best way to do that is to offer formal and informal ways for clients and community members to provide feedback about the work that you do. That’s why COA highlights the importance of stakeholder involvement in performance and quality improvement systems in its standards. As an organization, you get a sense of what’s working and what’s missing the mark. You can then tailor your services and outreach efforts to ensure that they are culturally appropriate. Most importantly, when you incorporate client and community feedback it makes those you serve active in organizational decision-making processes and promotes engagement and empowerment.

Conduct a community needs assessment

Conducting a community needs assessment is an effective way to identify strengths and resources in your community. It also highlights current gaps and service needs. Collaborating with community partners can enhance this assessment. You can also review other external needs assessments conducted by organizations with a community-wide focus. KIDS COUNT data center, a project of the Annie E. Casey Foundation, allows you to access local, state, and national level data and statistics on demographics and child and family well-being that can be incorporated into your assessment process.

Incorporate community demographics into your strategic planning process

Strategic initiatives should be responsive to changing community demographics and service needs. COA recommends that organization leadership review a demographic profile of their defined service population at least once every long-term planning cycle. However, it’s not enough to collect and review demographic data; it must inform an organization’s planning and operations. Promote cultural competence by establishing goals and objectives that are culturally appropriate for those you serve. Want to go a step further? Incorporate a cultural competency plan into your strategic planning process.

Foster a culturally responsive workforce

Promote cultural competence by having a diverse and inclusive workforce. A first step is ensuring that your human resources practices are culturally appropriate. Organizations should strategically recruit and employ personnel that reflect cultural characteristics of the service population. Is this a challenge for your organization? Create a plan that establishes goals for recruiting and employing individuals that represent your service population and community.

Another way you can commit to promoting cultural competence is by providing relevant education and training opportunities to personnel at all levels. Opportunities should not only focus on work with clients, but also address the internal workplace and interactions amongst other staff. Education and training should be tailored to the needs of your organization, but may include: language classes, interpreter training, mentoring programs, and diversity workshops. You can also conduct workforce assessments to inform ongoing personnel development opportunities to ensure that all staff is trained on culturally responsive policies, procedures, and practices. Once personnel have the necessary education and training, it’s time to integrate culturally responsive practices into everyday work with clients. As a provider, your goal should be to provide respectful, effective, and equitable care. This stems from adopting a service philosophy that is culturally responsive to those you serve, and culturally appropriate program-level policies and procedures.

Arguably one of the most important things that you can do as an organization is create safe and supportive environment where personnel can explore and gain an understanding of different cultures. You can do so by creating a cultural advisory committee to address workforce diversity issues or holding “cultural conversations” where staff can discuss diversity issues and learn from one another. Offering these types of forums reinforces a culture that is accepting and responsive to diversity.

Establish and maintain a diverse and inclusive board

One major responsibility of a nonprofit board is establishing and adopting organizational policy. Policies and procedures that support culturally responsive practice provide the framework for being a culturally competent organization. That is why having a board that reflects the demographics of the community it serves is so crucial. It’s no secret that board recruitment can be a challenge. If your organization is struggling to establish a board that is diverse and inclusive, establish a stakeholder advisory group that is representative of the community you serve and create a board recruitment plan that outlines strategies for getting everyone at the table. Need a little guidance? BoardSource is an excellent resource on board diversity, equity, and inclusion.

Are you feeling overwhelmed?

Don’t be. One of the most important things for organizations to keep in mind is that cultural competence is an evolving, active process; it’s not something that is attainable overnight. In fact, some researchers say there is a cultural competency continuum. The takeaway here is that every step you make towards becoming a culturally competent organization is a step in the right direction.

Want to learn more?

There are plenty of resources floating around the Internet that address cultural competence. Here are a few that you may find helpful:

The National CLAS Standards are a set of guidelines that aim to reduce health care disparities and advance health equity. COA developed a crosswalk to demonstrate how COA standards align with the National CLAS Standards and support the provision of culturally and linguistically responsive services.

National Center for Cultural Competency (NCCC)

The National Center for Cultural Competency (NCCC) aims to promote health and mental health equity through the promotion of culturally and linguistically competent service delivery systems and offers a variety of resources and publications geared towards the promotion of cultural competence.

Standards and Indicators for Cultural Competence in Social Work Practice

Are you a social worker? The National Association of Social Workers (NASW) developed standards and indicators for cultural competence in social work practice.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA)

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) provides a host of information around cultural competency in the field of behavioral health. Check out this manual which focuses on helping providers and administrators understand the role of culture in the delivery of mental health and substance use services.

Okay, your turn!

What are some challenges your organization faced in this area and how have you attempted to overcome them? Can you share any tips, tools or resources that lead to your success? Please leave a comment below and help others learn from your experiences.

When beginning the accreditation process – specifically the completion of the Self-Study – one of the most intimidating challenges can be trying to figure out how to organize the work and delegate it to your staff. You don’t need a certificate in project management to accomplish this task (although having one won’t hurt!). What you do need is prep time, focus, and a solid understanding of what’s expected.

This post will discuss how to form effective workgroups that can assist your organization with completing the necessary work in order to achieve accreditation – and hopefully improve your organization’s operations as well. Now let’s get started.

When talking with organizations in COA’s network, we see a variety of types of workgroups. Some small organizations do not form new workgroups; they simply utilize a currently existing structure to fill the role. On the other hand, large organizations may develop multiple workgroups that focus on different aspects of the Self-Study. Only the organization can determine what the best model is going to be, but we can certainly explore some basic characteristics.

According to Kozlowski, S. W. J., & Bell, B. S. (2013), workgroups have the following qualities:

- They consist of two or more people

- Their participants are part of the same organization

- They have a common goal

- Their tasks are completed together and individually

- They involve social interaction

- They retain boundaries established by the organization

- They are part of the culture of the organization

One is the loneliest number

If your workgroup only consists of you thenyou should probably revisit your plan to achieve accreditation. Even for small organizations, all levels of staff should be involved in some way. There are multiple benefits to involving many people. First off, staff will have a better understanding of the importance of accreditation if they are embedded in the process. If the process is presented to them in a positive way then they can take ownership. A common question is “how can you present accreditation to staff in a positive way?” While it’s difficult to imagine how anyone can view accreditation in a negative light, talk with your staff – particularly those that you want to engage in workgroups – and bring the focus to achieving client outcomes. The purpose of accreditation is to improve outcomes for those that receive your services. Every action that takes place in accreditation should be tied to the end user: the consumer.

Another way that staff can buy-in to participating in a workgroup is to view it as a professional development opportunity. In fact, you would be remiss if you didn’t. Think about your shining case managers, clinicians, administrative assistants, residential managers, and foster care workers who have impeccable paperwork, organized with to-do lists, and always volunteer for new projects. Working on COA-related activities can improve their administrative and leadership skills, expand their knowledge of social service management, and program development.

“Every action that takes place in accreditation should be tied to the end user: the consumer.”

A chance for collaboration!

Another commonality in workgroups is that they are all part of the same organization. Note that it’s within the organization, but not necessarily within the same department, division, or satellite office. Workgroups foster cross-departmental collaboration. For example, let’s say that you are going to create a workgroup that focuses solely on drafting and reviewing procedures for the organization. For medium-large organizations, having this type of committee helps ensure that there is consistency across the organization, standards are still being met, and duplications are avoided. Including staff from different departments and different levels can provide different perspectives. Perhaps a member of management reviews a procedure and thinks “wow, this is great and will really help improve the reliability of our data.” Then a member of the direct service staff, who is also part of this committee, reviews the same procedure. She may have a comment such as “the intent of this procedure is spot-on, but the ability to put this in practice is unrealistic.” What’s better than a well written procedure? – A procedure that is actually practical. Having a diverse group of individuals within your organization as part of the accreditation workgroup is essential to change that is effective.

Find common ground

Common goals are an essential characteristic of workgroups. Having common goals relates to proper planning. If you establishing one committee or 3 committees to complete the work, there needs to be a goal that is achievable. You may think, “The goal is to get accredited.” Good point, that is the goal, but that’s the goal of the entire organization; not of the workgroup. The workgroup’s goal may be to establish a working PQI system, assess current practices to COA standards, or assemble the Self-Study. The goal of each workgroup will clearly delineate its role in completing the larger mission: achieving accreditation – and as we discussed earlier - to improve outcomes for consumers.

To further break down the goal, we need to identify specific tasks that support the actual completion of the workgroup’s goal. Planning, again, comes into play. Recognizing that planning is not everyone’s strong suit, there are some resources out there to assist. While COA doesn’t endorse any specific resource, we do find these helpful. Meister Task is an efficient task management application that can be used to organize individual tasks as well as collaborative tasks. Consistent with our definition of workgroups, there are both individual tasks and tasks that people must work on together. This web application can help support and provide structure to both. Another great application is Wunderlist. It provides some of the same functionality with a different style. If you are not quite ready for that level of organization and need some foundational support, try reading Getting Things Done: The Art of Stress-Free Productivity by David Allen. It’s an easy read that will help you organize your life, as well as your accreditation work. Remember, if you do utilize any of these resources, it’s recommended to take a full day to sit back and focus on implementing these systems for your work.

Assigning the work

However you handle the workload, a workgroup has tasks that are completed individually and some that are completed by more than one person or a subgroup of the committee. When tasks of the workgroup are being assigned to its members you will want to consider the strengths and weaknesses of each member. Initially, it may be your gut reaction to assign tasks that are good matches to individuals’ strengths; however, also consider matching someone’s weakness to a task to help them further develop. Perhaps pairing that person with someone who does have more experience can be a great learning opportunity. Make the most out of your accreditation experience and use it to support a positive learning environment. Maybe you can even develop mentorships within your staff, with the accreditation work as the central theme.

Involve social interaction, have you ever tried to hold a committee without social interaction? Typically that’s an email with directives to everyone involved with no discussion. Sometimes effective; most of the time not. At the beginning of the process of forming your workgroups, you will be concurrently developing the buy-in of the workgroup members. Meeting in-person, with sugary treats, that typically helps (personal favorite: Insomnia Cookies). If you can’t have fresh cookies delivered, consider holding the meeting outside of your organization, at least for the first time. Use this common goal, develop strong collegial bonds that last past COA Accreditation. And finally, manage your meeting efficiently. Here are some tips from Mindtools.com.

Introducing accreditation to your culture

Maintaining boundaries that are consistent within the organization may be a little bit more challenging for an accreditation workgroup. The group may be perceived by others in the organization as closed-off or working on something has nothing to do with the rest of the staff. One remedy for this perception is to provide communication about the status of the workgroup throughout the process to the rest of the organization. The workgroup is not charged with setting completely new and rigid policy, determining who at the organization is underperforming, or planning a coup d’état. Transparency is key, solicit feedback from staff who may not be directly involved. Always ask for volunteers, although don’t expect a waitlist. The accreditation workgroup is not a clique; it is a model for how people work as a team to achieve a seemingly insurmountable task.

Lastly, it is important to maintain key components of the organization’s culture. You can expect shifts, bumps and slides during the process, but the core of your organization will grow stronger. Your culture is the cornerstone of stability for your staff, who spend 40 hours of their lives there each week. It is a safe place for consumers whose lives you change. It is part of the connective tissue that holds your community together. Change may be inevitable but the culture of your organization is the reason for your continued success.

Share your tips!

What tips do you have for developing a strong workgroup or sustaining it once it is in place? Please leave a comment below and help others learn from your experiences.

!["We have really enjoyed the fact that we are united by the power [of] COA accreditation and by sharing our common mission [of] providing children and families, in a contexual and in a multicultural approach, with the best." -Jorge Alberto Acosta, Founder of Nuevo Amanecer Latino Children's Services](https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5817757515d5dbcebad2b0bc/t/5c758d43f9619ac702a6edb4/1551207752285/Copy+of+Benefits+of+Accreditation+Pull+Quotes+%285%29.png?format=1000w)