If someone were to rate their wellness level, their first instinct might be to measure their physical or mental health against common indicators, such as the presence of an illness or injury. These markers are a good place to start, but one’s health status does not happen in a vacuum independent of their environment.

As the United States continues to find its healthcare system under fire, one issue many point to is the health disparities mediated by race, ethnicity, geography, orientation, socioeconomic status, etc. Both level of education and socioeconomic status have direct correlations to health status, with individuals living in poverty eight times as likely to have poor health outcomes. As recently as April 2018, the New York Times reported on significantly high mortality rates for America’s Black mothers and babies in comparison to their white counterparts and how that relates to their lived experience.

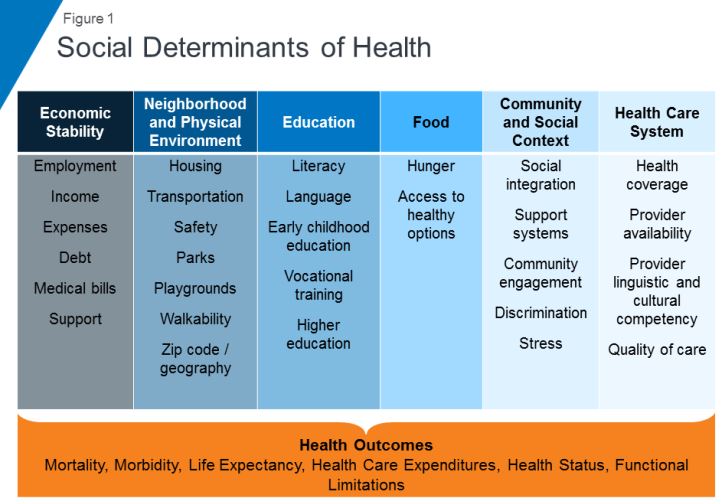

Often times your health is influenced by factors beyond the individual’s control, factors related to their social context. Health professionals refer to these as social determinants of health (SDOH) and they have become the focus of increasing interest when it comes to closing the health disparity gap and taking more proactive approaches to population health and well-being.

Defining SDOH

SDOH refer to economic and social conditions and their distribution among the population thus influencing individual and group differences in health status. They are factors found in one’s living and working environments rather than individual risk factors such as behavior or genetics, which can impact one’s vulnerability to disease.

The Center for Disease Control (CDC) and the World Health Organization (WHO) have both emphasized the importance of taking into consideration the conditions in which people live, learn, work, and play when assessing health status. WHO frames the potential for these experiences to be health-damaging as “the result of toxic combination of poor social policies, unfair economic arrangements, and bad politics,” calling for society to look beyond the health sector when dealing with issues of health and disease.

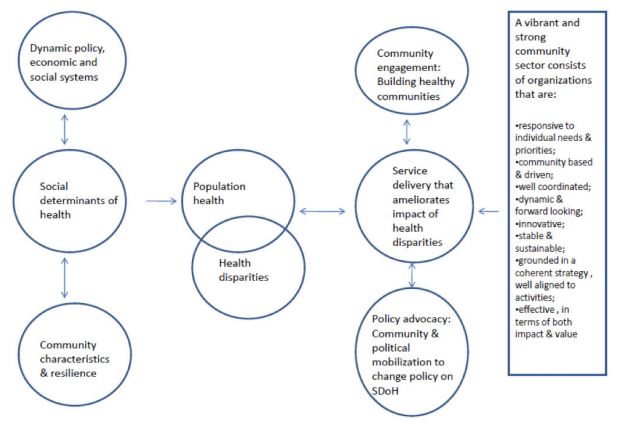

Audrey Danaher, from the Wellesley Institute, created a framework to describe how these social determinants may play upon each other given that the impact is not direct, but mediated. For instance, community characteristics and resilience can have an effect upon SDOH independent of policy, economic, and social systems. A responsive community sector (e.g. non-profit organizations that provide services within communities to meet needs) can help to reduce the disparities through engagement, advocacy, and service delivery. It is worth noting that Danaher’s data and framework comes from communities in Canada, which has universal, single-payer healthcare, further supporting the argument that individual health goes beyond just healthcare.

SDOH on individuals’ health

SDOH play a significant role in individuals’ health outcomes, and research has demonstrated that there is a social patterning of disease. Per Williams, Sternthal, and Wright (2009), “disadvantaged social status predicts higher levels of morbidity for a broad range of conditions in both children and adults.” Growing up in economic poverty in and of itself is correlated with a broad range of health-damaging conditions (e.g., family turmoil, neighborhood violence, consume polluted water and air) and growing up as part of a marginalized community increases your exposure to psychological stressors. But how do these things in turn play a role in individuals’ health?

Let’s look at asthma. While the consumption of polluted water and air increases the risk of asthma within the population, this alone does not fully account for this disparate distribution childhood asthma. In a 2017 study, researchers found that African-American children living in lower socioeconomic neighborhoods were 8.8% more likely to have asthma than their white counterparts, 6.7% more likely in middle-class neighborhoods, and 5.8% more likely in affluent communities. Not only are there differences among racial lines, but youth in more deprived communities are significantly more likely to have asthma emergency department visits and significantly more asthma inpatient admissions. Some SDOH identified as playing a role in these group differences include maternal stress during pregnancy, living in communities with higher levels of violence, overburdened or absent social supports, and psychological morbidity.

Another example of a SDOH is food insecurity, defined by the U.S. Department of Agriculture as a lack of access to enough food for an active, healthy life. Food insecurity is caused by a number of elements such as income and unemployment, disability, and food deserts, which are associated with both socioeconomic status and race/ethnicity. Food insecurity does not necessarily cause hunger, although it is a possible outcome, but it is tied to chronic disease such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes.

Community sector in action! Connecting SDOH to service delivery

Community sector initiatives have often taken the lead in responding to deprivation and negative SDOH. Due to the nebulous nature of SDOH and how they’re specific to different communities and populations, it makes sense that change comes from within the community itself. Just as communities can be a cause for poor SDOH, they can also be the catalyst for improving them and thus improving the community’s outcomes.

Majora Carter’s environmental justice work in the South Bronx is an excellent example of a community-driven response to SDOH. The South Bronx is home to a significant number of industrial plants, including waste processing (40% of the city’s waste and 100% of the Bronx’s end up there), sewage treatment, and four electrical power plants. It has the lowest ratio of parks to residents throughout the entire city; it ticks all the marks on social determinants of health listed above as well as the poor corresponding outcomes. Carter started with the goal of creating a new park, which subsequently led to a greenway movement. One of her next moves was to secure funding for a waterfront esplanade that allowed for a wider range of forms of transportation, thereby influencing policy on traffic safety in the area. Using social capital, she also created facilities that would not only bolster the health of residents in the community but improve quality of life (e.g., encourage residents to be more active) and create opportunities, such as green-collar jobs and community business investment. By recognizing and focusing on the impact of the environment on the health and safety of its inhabitants Carter was able to develop solutions to improve the health of her neighbors.

Carter’s success is not isolated. COA accredited organizations are the community sector and often occupy the spaces needed to rehabilitate SDOH. While this not has always been an explicit or even conscious goal of human and social service delivery, if you look at the SDOH listed in the graphic above, you can map the services provided by COA accredited organizations onto the list. Whether it’s providing youth with alternatives to out-of-school suspension, offering assistance with navigating the healthcare system, or providing housing and community resources in a supported living program, all of these solutions fill gaps in the community and boosts their SDOH.

Next steps

This wouldn’t be a COA blog post without a few ways in which you can get involved. Here are a few initiatives working to improve social determinants of health:

One of the most powerful actions you can take is to get involved with your own community. What are some of the issues you see around you? What are some of the areas that need further support? Are there grants from your city to help implement the changes needed? Chances are, there are already organizations working towards improving community health outcomes with opportunities to volunteer or partner.

In the high-intensity, resource-scarce universe of human services, the service environment itself often gets overlooked, or else overshadowed by compliance concerns. Against the backdrop of serving families at risk, individuals in crisis, and struggling communities, all while trying to keep the doors open, space planning concerns like layout, furnishings, lighting, and décor can seem trivial. Facility design might sound like a luxury, but in reality it has a presence in almost every aspect of service delivery. The evidence is clear. The physical environment can have a profound impact on behavior, mood, perception, and accessibility. When designed intentionally and strategically, your facility can support the work and mission of the organization. Left unexamined, it can limit or even undercut your impact.

Whether you’re opening a new site, considering a relocation, planning a renovation, or just looking for ways to refresh your facility in a way that improves the effectiveness of your services, here are some important issues to consider:

Safe space

The most fundamental concern for every organization is safety. Every facility has to comply with building codes and regulations aimed at protecting occupants from hazardous conditions. Features like emergency exits are specifically designed to promote safety by influencing behavior in the event of a critical incident – such as evacuating during a fire.

Serving vulnerable populations, however, often means preparing for and responding to critical incidents stemming from distress, conflict, and harmful behavior. In recent years suicide prevention has become a focal point for facility planners and is emerging now as a powerful example of how the built environment can be leveraged to save lives. Organizations serving populations at risk for suicide are embracing the imperative to scrutinize all architectural features, fixtures, and materials in the service environment for their potential to become an instrument for harm – specifically as an anchor point or ligature. Shatterproof glass, round-edged doors and tables, breakaway curtain and closet rods, and tamperproof power outlets are just a few examples of features that have been designed to be suicide-resistant. The layout of the service environment can also play a role in reducing opportunities to self-harm; placing staff areas in close proximity to high-risk individuals allows for consistent yet non-intrusive observation.

A trauma-informed approach tells us that identifying and addressing triggers or trauma reminders is key to preventing and de-escalating crisis situations. Organizations must examine both the physical and psychological safety of their facilities and keep in mind that the built environment itself can be a trigger or stressor. An enclosed, restrictive space can often be triggering for individuals with trauma histories or individuals with certain mental disorders, such as schizophrenia; this is often addressed by foregoing corridor layouts and installing glass doors that enable individuals to get a clear view from one service area into the next. Planners also often avoid using the color red to avoid associations with blood, fire, and emergency lights that can trigger a trauma response. Individuals coping with anxiety or PTSD can be overstimulated by patterns, brightly contrasting colors, or other visually complex designs; neutral or softer colors with more subtle transitions are therefore generally more appropriate for therapeutic environments.

While safety is imperative, there are plenty of other ways the built environment intersects with organizational goals and priorities. Now that we’ve looked at how the physical environment can reduce suicide, harmful behaviors, stress, and aggression, we can turn to how it can reinforce and encourage positive behavior and promote better client outcomes.

The client experience

A well-planned facility should complement your organization’s work by ensuring that individuals and families feel safe, supported, and in control while they are receiving services. To learn more about how organizations use the built environment to support their work, we spoke with Children’s Institute, Inc. (CII) in Los Angeles, a COA-accredited organization that provides a broad array of mental health, early care and education, child welfare, family support, and youth development services to children and families – who are also currently in the process of relocating one of their sites and constructing a new campus.

A client-centered approach informs many of the crucial decisions CII has made in identifying and designing their new facilities. “We thought about how it would affect the client’s experience, being on one floors or two,” says COO/CFO Eugene Straub. CII has been careful to ensure that their facilities are welcoming to both clients and staff. “The goal is building a sense of trust and security. The last thing you want to do is make anyone feel uneasy.” Improvements have also been made to existing sites where the space was not meeting families’ needs. “We had a nice lobby and waiting areas but there were no activities, and we looked for ways to change that and make the space more inviting and inspiring.” Now CII’s once-empty waiting areas include a lending library and creative space for children and families to use.

What are some ways that your organization could find inspiration and ideas when planning facilities? Your service recipients, staff and community are a great resource for ideas and a great place to start. Organizations should always look to their service recipients and their communities for ways to enhance their service environment, and tailor their facilities to the unique needs of the service population and to their service model. For example, a residential facility for individuals with schizophrenia can provide some relief to residents coping with paranoia by orienting beds and desks to face the door. A youth development program for children with autism spectrum disorder, who often struggle with spatial navigation and wayfinding, should consider applying visual cues to transitional spaces. Every organization’s approach to designing an effective and supportive service environment will be unique and depend on their scope, service population, service model, and culture. But there are a few universal design features that facility designers and environmental psychologists agree contribute to a calming, welcoming, and therapeutic service environment:

Nature equals nurture

Studies have consistently shown that access to nature, whether physical or visual, has a calming effect. Treatment facilities often situate themselves in a natural setting for this reason, but any organization can look to existing assets to bring to their full potential, such as a small outdoor space that can be converted into a courtyard or garden, or installing windows to take advantage of a good view. Organizations that are truly limited can still make enhancements by incorporating plant life into the decor and displaying nature and landscape art, which have also been demonstrated to have a positive and calming effect on mood.

Let the sun shine

Sunlight triggers the release of serotonin, which boosts mood and focus. Research also indicates that the ability to identify time of day through observed sunlight is conducive to re-establishing perception and natural thinking while minimizing disorientation. Natural light also makes small spaces appear larger and more open than they are. Organizations should ensure that they’re maximizing and not obstructing their natural light, such as by moving furniture away from the windows, using window coverings that filter rather than block out sunlight, and opening up any doors and windows that would allow natural light to pass through the facility. Transom lights (windows built into the space above a door) and skylights are also examples of architectural features that maximize sunlight while still preserving privacy.

Power to the people

A client-centered and trauma-informed approach to services stresses the importance of giving service recipients opportunities to have a voice in their service plan and at each stage of service delivery. For survivors and individuals coping with past trauma, opportunities to take control and make their own choices are important exercises in self-empowerment and essential steps on the road to recovery. Current best practice regarding residential facilities stipulates that residents should already be encouraged to personalize and decorate their own space. However, when possible, personal choice should also be extended to the environment by giving service recipients the power to customize lighting, temperature, acoustics, or furniture arrangements. To balance flexibility with safety, facility planners often choose furniture that is too heavy to be thrown or used as a weapon, but that can still be moved around and reconfigured, which gives individuals (or groups, in communal settings) autonomy to situate themselves where they feel safest.

No place like home

Experts typically agree that a safe, therapeutic, non-institutional and homelike environment is the best setting for residential treatment. Some strategies that designers employ to make a facility more warm and inviting include using upholstered rather than hard furnishings to invoke a softer, cozier feel, and mixing and matching a cohesive array of furnishings to avoid a uniform, institutional look. Given that “home” is a cultural construct, cultural competency is vital to ensuring that your environment meets the definition of “homelike” for your service population.

Of course, “home” is about more than just furniture — it’s also about people. When designing or evaluating a facility, organizations must consider not only the service recipient, but their support network. Because an engaged and committed support network is one of the most important contributing factors to positive client outcomes, service environments need to promote and facilitate their ongoing involvement. Organizations should be mindful that an imposing service environment can discourage or inhibit the service recipient’s support network, and evaluate whether their facility accommodates and encourages visiting family and friends as well as any collaborating service providers. Is it intimidating for visitors to access or navigate the facility? Are there welcoming spaces for residents to spend time with their visitors, or to have private conversations?

Supporting your staff

Getting your space to work for your service recipients also means ensuring that it works for your workers. As with service recipients, the environment influences workers’ behavior, mood, and functioning – which in turn impact performance and productivity, and your organization’s effectiveness. In human services, an ineffective environment undermines not only your bottom line but your mission.

The human services field also faces significant workforce challenges – namely recruitment, retention, and secondary trauma. Qualified workers are in short supply, in no small part due to poor funding and stigmatization of the service population. Staff shortages and the difficult nature of the work, which often manifests as secondary or vicarious trauma, lead to burnout and to high rates of turnover. Finally, worker turnover negatively affects client outcomes.

These workforce challenges have been at the center of the design and planning process for Children’s Institute, Inc.’s new offices. With the aim of promoting collaboration and “addressing the adverse effects of the work itself”, CII decided to eliminate cubicles in favor of a communal, team-driven open plan layout that will allow staff to support one another, celebrate their successes together, and foster staff resiliency. Straub observed that the cubicle layout often forces staff “to go from meeting with clients to sitting at their desk by themselves” and process their experiences in isolation. The intent of the new layout is to encourage workers to “have more of a shared experience and focus on wellness and self-care both individually and with each other”. The new offices also feature “decompression zones” – calming work-free spaces for staff to recover, including through meditation and yoga, as well as larger common areas, kitchens, and breakrooms. Evolving workplace norms mean that “the younger workforce wants an office space that fosters support and feels less corporate and more collaborative,” Straub explains, making these amenities not just “perks”, but rather, vital resources that will promote staff wellness and strengthen recruitment of valuable staff.

CII is also allocating space for “drop-in” staff – workers from other sites who are out in the field will be able to use nearby CII offices as a landing spot in between client visits. Straub envisions that this increased “cohabitation” will stimulate knowledge and resource-sharing and enhance linkages for families and continue to build the culture of the agency. Emphasizing the importance of “collaborating with the end user,” CII has also been careful to engage staff in the facility planning process, bringing all staff to tour the new space before signing the lease and soliciting feedback about the environment as part of annual employee surveys. Continuous assessment of a new or revamped workspace is not just good quality improvement practice, it also ensures that the organization identifies and addresses any unforeseen effect on employee functioning. For example, in an evaluation study of behavioral health facilities, researchers discovered that staff in a new facility that had been designed to promote client-staff engagement were experiencing greater burnout in response to the increase in client interactions.

Strategic plans to building plans

Creating a safe, effective, and supportive service environment requires the organization to approach the physical environment as part of its mission. It calls for not only commitment and investment, but also a shift in attitude — away from “being happy just to get the space”, as Straub says, and towards leveraging the space to influence how the organization’s operations are experienced and perceived. By tying together their facilities, mission, and strategic plan, CII’s ambitious expansion project received enthusiastic support from its board and funders. Straub sees the new campus as “an opportunity to create organic change” by leveraging the space to build partnerships with the community; plans are already underway to co-locate with other providers and host community taskforces and other grassroots organizing initiatives.

As much as we’d like the primary takeaway here to be “good facility design is not about aesthetics”, it bears noting that a well-designed facility achieves through its appearance two invaluable objectives: firstly, it destigmatizes the organization’s services and service recipients, and secondly, illustrates the depth of the organization’s commitment to the community.

Tell us in the comments: How has your organization used its facilities to support service recipients and staff? What would you change about your current service environment?

Further reading

Building Better Behavioral Health Care Facilities

Rethinking Behavioral Health Center Design

Designing for Post-Traumatic Understanding

6 Behavioral Health Design Trends

Can a Frank Gehry design help change the dynamic of Watts?

Thank you to Tiffany Langston of the Nonprofit Finance Fund for this guest post!

History of the survey

In 2008, the economic downturn created an atmosphere of fear and uncertainty, not just for individuals, families, small businesses, and corporations, but it was also a very scary time for nonprofits and their clients. At Nonprofit Finance Fund (NFF), we wanted to find a way to tailor our financing and consulting services to be the most helpful to charitable organizations. How could we offer support, tools, and resources, so that nonprofits could navigate this tricky time? We decided to ask nonprofits how the changes in the economy affected their bottom line and the ability to serve their communities. The State of the Nonprofit Sector Survey was born.

Nonprofits are a linchpin in creating social good. Yet there is precious little collective, real-time data on how nonprofits are doing. Are they serving more clients or fewer? Do they have the resources they need to do their work? Are they opening new offices, or dangerously close to closing their doors?

We launched the first Survey in early 2009, with little fanfare and almost no promotion. We rolled up our sleeves, opened our rolodexes, and asked our networks to spend 15 minutes to tell us how they were feeling, what they were doing to combat the recession, and how NFF could help them deliver on their missions. We heard from 986 respondents, many of whom told us that they were feeling financially vulnerable, bracing for funding cuts across the board, preparing to end the year with a deficit, and developing a ‘worst-case scenario’ contingency plan. The recession brought into focus a serious, long-standing issue: the nonprofit sector is continually forced to do more with less, and the margin between stability and crisis is often precariously razor-thin.

But the thing that surprised us most was the numerous requests we got from media, researchers, policymakers, nonprofits, and funders, to do a deeper dive into the data. The results were published in The New York Times, CNN.com, and The Chronicle of Philanthropy. There was a thirst for real-time data, and at the time, no one else was doing this type of survey on a national scale.

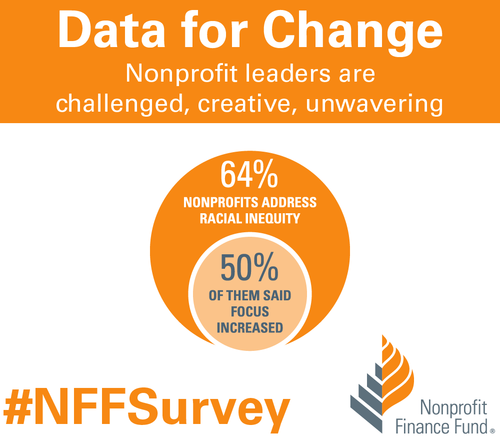

Over the years, the questions adapted as the sector changed. It became a widely-watched barometer of US nonprofits’ programmatic, operational, and financial health. In 2010, we found that while the economy was recovering from the recession, nonprofits were not having the same success. By 2011, 87 percent of the 1,935 respondents said they still felt like the recession hadn’t ended. In 2012, we started asking about government grants and contracts, and if nonprofits were getting paid on time. The outlook finally started to improve by 2013, and we inquired about how organizations collected data and measured impact. And this year, we asked nonprofits about the diversity of their senior leadership and board members, and if their organizations proactively address racial inequity.

State of the nonprofit sector survey 2018

We are living in volatile times. As we prepared for the 2018 Survey, we were excited to get the pulse of the US nonprofit sector and better understand the challenges organizations now face. The 2018 State of the Nonprofit Sector Survey opened on January 16 and closed on February 28. We heard from 3,369 leaders across all 50 states and a wide range of sizes and missions. Respondents said they’re facing chronic challenges and real-time concerns, remain resilient and committed, but are worried about the vulnerable people they serve.

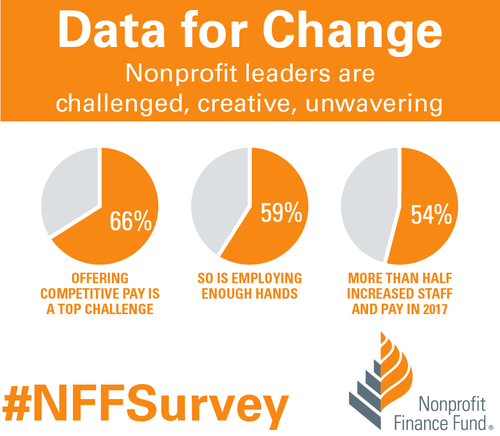

When asked about 2017, 79 percent of respondents saw an increase in demand for services, and 86 percent anticipate an increase in the coming year. Not only did 57 percent of nonprofits find it difficult to keep up with the rising demand last year, but that number swells to 65 percent for organizations serving low-income communities. Despite the challenges, nonprofits continue to invest in programs, staff, and strategies. We found that 52 percent of respondents said their organizations expanded services in 2017, and 63 percent plan to do so in 2018. We learned that 54 percent of responding nonprofits increased staff and 55 percent increased compensation in 2017. We found that 64 percent said they address racial inequity, and half of those said that focus grew in 2017. We also learned that 76 percent of responding nonprofits finished 2017 at break-even or better.

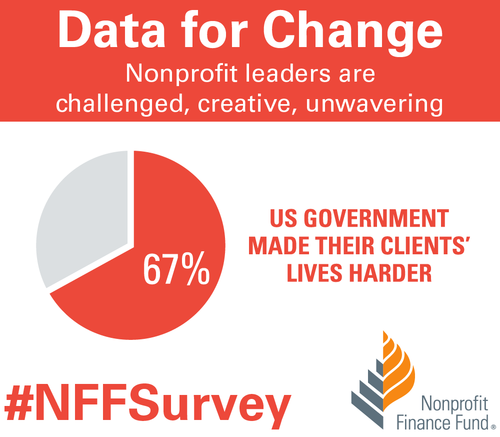

Affordable housing was the most-cited critical community need, followed by youth programs, mental and behavioral health services, and financial capability. We also asked nonprofit leaders how the federal government’s policies & positions influenced the communities they serve, and 67 percent said those practices make their clients’ lives more difficult. Additionally, 37 percent of respondents said their organizations plan to formally engage in policy/advocacy in 2018.

How to use the data

At NFF, our mission is to create a more just and vibrant society. One of the ways we work toward that is by sharing accessible insights, so that the sector has the necessary data to make informed decisions. You can explore the Survey results completely free of charge using our Analyzer. Compare your nonprofit to peer organizations across focus areas, sizes, and geographies. Use the findings to inform planning around strategy and budgeting. Cite data in your campaigns, white papers, testimonials, and grant proposals. Use the data as evidence to support open discussions with funders about the full costs of service delivery and meeting the needs of your communities.

We invite you to dig into the data. Use the filter or combination of filters that gives you the right slice of information for your presentation, board meeting, or application. You can even download images of the visualizations and drop them right into a slideshow or report. Please let us know how you’re using the findings to deliver on your mission. Email us, or share on social media using the hashtag #NFFSurvey. Thank you to everyone who took the State of the Nonprofit Sector Survey, entrusted NFF to raise your voices, and contributed to this critical social sector data set.

The views, information and opinions expressed herein are those of the author; they do not necessarily reflect those of the Council on Accreditation (COA). COA invites guest authors to contribute to the COA blog due to COA’s confidence in their knowledge on the subject matter and their expertise in their chosen field.

Tiffany Langston

Tiffany Langston is the Associate Director, Knowledge & Communications at Nonprofit Finance Fund. She has worked at the intersection of nonprofits and philanthropy for nearly a decade, including overseeing digital communication efforts for WaterAid America and Philanthropy New York, respectively. She is a food lover, writer, and her work has been nominated for a James Beard Foundation Journalism Award.

You are probably familiar with the ripple effect. The term refers to a sequence of events that is triggered by a particular incident or occurrence. The most common example is dropping an object into a body of water…let’s say a stone in a lake. Once it falls, the stone causes a series of waves that spreads across the body of water, the waves ever expanding their reach. The metaphor is often used to describe the potential impact that our actions have on others and the world around us. At times, we may not even be aware of the ripples that we set in motion.

There is no better way to describe the current opioid epidemic. Opioid dependence doesn’t just affect the individual user; it touches the lives of those around them, leaving its mark on children, family members, and friends. And it doesn’t end there. The ripples grow and extend to countless sectors.

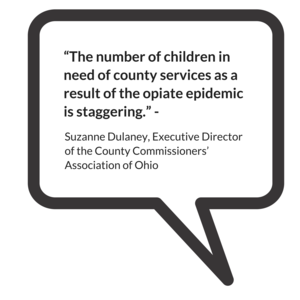

One system that is feeling the impact of the opioid epidemic is child welfare. Reports from public officials, advocates, and those working in the field echo the same sentiment – the current crisis is overwhelming. As opioid abuse continues to increase nationwide, the demand for foster care placements is also on the rise. This leads us to wonder what is the relationship, and what does it mean for families and future generations of children?

In recognition of National Foster Care Month, this article will shed light on the connection between the opioid epidemic and child welfare and contribute to the ongoing dialogue on how policy and practice can better support those working with families entrenched in this devastating crisis.

The scope of the problem

Opioid use disorders and fatalities continue to rise

There has been a sharp uptick in the use of opioids since 2010. According to SAMHSA, in 2016, 2.1 million Americans had an opioid use disorder (OUD). As that number continues to rise, so does the number of fatalities. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports that 115 Americans die from an opioid overdose every day.

The number of children who have parents struggling with OUDs is unknown. However, a 2017 analysis yielded that 1 in 8 children resided with at least one parent who had a past year substance use disorder (SUD). The report also found that 1 in 35 children lived in a household with at least one parent who had an illicit drug use disorder. Unfortunately, it leads us to consider that parents are among those that we lose to the opioid crisis on a daily basis.

Foster care placements are increasing

Concurrently, as reports of opioid use rise, the demand for foster care placements across the country has also grown. The number of children entering foster care was on a steady decline for more than a decade; however, the tide shifted in 2012. From fiscal years (FY) 2012-16, the number of children in foster care nationally grew by 10%. While individual states varied, more than two-thirds experienced a surge in foster care caseloads during this period. Six states – Alaska, Georgia, Minnesota, Indiana, Montana and New Hampshire – saw foster care populations rise by more than 50%.

More children are residing with grandparents and relative caregivers

Another recent development is the growing number of grandparents taking on the primary caregiver role. Generations United reports that about 2.6 million children – 3.5% of all children nationwide – are being raised by grandparents or relatives across the country. When we look at the data, 32% of children in foster care are being raised by kin, more than previous years. And that may be just the tip of the iceberg. It is estimated that for every child in foster care with relative caregivers, there are 20 children being cared for by grandparents or other family members outside of the foster care system.

Parental substance abuse is a contributing factor for out-of-home placements

What contributes to the need for out-of-home placements? According to the latest national data, parental drug abuse is a factor in roughly one-third of all child removals. While the proportion of children entering foster care due to these circumstances appears to have remained steady over the past few years, it is increasing. Looking across the different categories for removal, drug abuse by a parent had the biggest percentage point growth between FY 2015 (32%) and FY 2016 (34%), which is notable in the face of the current epidemic.

Connecting the dots

So…is there a relationship between the opioid epidemic and child welfare, and if so, what is it? It’s complicated.

Given the timing of these trends, it is hard to imagine that increased opioid use doesn’t play some role in rising foster care caseloads. A recent national study found that counties with higher substance use indicators (drug overdose deaths and drug-related hospitalizations) have higher rates of foster care entry, indicating a relationship between child welfare caseloads and substance use prevalence. However, we have to remember that correlation does not automatically equal causation (proof that what you learn in statistics will come back around) since we can’t control for all demographic and socioeconomic factors and their potential influence on out-of-home placements.

Even though the increase in foster care and relative care placements has been attributed to the opioid epidemic, empirical evidence to prove cause and effect is lacking. This is in part due to the way that the federal government and states track data on child removals, more specifically the contributing factors. For example, there is national-level data on the number of children being removed due in part to parental drug abuse, but it isn’t broken down in a way that shows what type of drug was being abused. Therefore, there is no way to know how many foster care placements stemmed from opioid abuse versus the abuse of another type of illicit drug.

Nonetheless, public officials, advocates and others working in the field are making a direct link between the opioid crisis and increased demand for out-of-home placements. Anecdotally, there are similar accounts across states of the opioid epidemic and its impact on communities. Child welfare agencies are seeing more children come into care because of parental opioid abuse, and children entering the foster care system are getting younger and younger. It has been reported that there aren’t enough foster homes to meet the growing need. Caseworkers are feeling overwhelmed by growing, multifaceted caseloads.

What does this all mean for children and families?

Substance use disorders impact on families

Let’s take a step back. To understand the ripple effect of the opioid epidemic, we have to first look at how parental substance abuse impacts child and family outcomes. At a foundational level, parents struggling with a SUD may not be able to provide for a child’s basic needs (e.g., appropriate supervision or nutrition). Equally troubling, a child can be deprived of emotional support and positive attachment, critical factors in healthy childhood development. Inconsistent parenting inevitability hinders stability in the home. For a child, life can become chaotic and unpredictable, both of which are associated with negative outcomes. That is why parental substance abuse is a known risk factor for child welfare involvement. A 2016 study found that when compared with their peers, children whose parents faced SUD-related issues were three times more likely to experience abuse (physically, sexually, or emotionally) and four times more likely to experience neglect.

Parental substance abuse and child trauma

We know that trauma experienced early in life can adversely impact a child’s development and have long-term health consequences, and parental substance abuse is a one form of childhood trauma (aka an adverse childhood experience or ACE). Often, substance abuse is compounded with other types of adversity, making the severity of potential negative outcomes even worse.

Research shows that history has a way of repeating itself. Children who grow up with complex trauma are more likely to struggle with substance-related issues. One study found that individuals with five or more ACEs were seven to ten times more likely to have issues with illicit drug use. Other explorations into the topic have yielded similar results. There are a host of reasons why people with past trauma experience are more vulnerable to developing a dependence on substance use. While not all children will experience such consequences, the risks to future generations are far too great and warrant immediate intervention. In order to break the cycle, we have to find a way to address the opioid epidemic that is trauma-responsive.

The role of child welfare

The child welfare system is poised to be a catalyst for change. Agencies are tasked with protecting children from maltreatment, abuse, and neglect, and in-home services play a critical role. In-home services are aimed at promoting the well-being of children by ensuring safety, achieving permanency, and strengthening families. When faced with familial challenges, keeping children with their parents is optimal (as long as it is safe and appropriate). Children do best in families with the support of at least one caring adult. Even in crisis, children can thrive when the right protective factors are in place. Removing a child from his or her home disrupts daily life and expectations. All of that instability can be traumatic. The stress that stems from coping with parental loss can have long-lasting effects on a child’s emotional, behavioral, and academic outcomes.

Parental substance abuse has long been an issue for child welfare agencies, one that is now amplified by the recent opioid epidemic. Child welfare agencies across the country are inundated with high caseloads. The complexity of the cases given the unique circumstances and service needs of families battling opioid dependence are adding another layer to an already challenging situation. Not to mention, family stabilization and/or reunification is complicated (contender for understatement of the year). Despite what we know about keeping families together, having children remain with their parents may not be in their best interest due to the impact that substance abuse can have on parenting, making out-of-home placements the safest option. What’s more, reuniting children with their parents can be tricky given ebbs and flows of recovery. The tug-of-war that this creates for caseworkers can be challenging to navigate. So, how do we support those working with families experiencing the crisis firsthand?

Where do we go from here?

Implement what works for families

States and localities are getting creative and implementing interventions that have proven effective for families, recognizing the trauma associated with parental substance abuse. There is ample support for family-centered treatment for substance abuse, including opioid dependence. Additionally, program models that focus on systematic change and cross-system collaboration have also been linked with favorable outcomes.

- Sobriety Treatment and Recovery Teams (START) is an intensive, integrated program for families experiencing co-occurring substance use and child maltreatment. START launched in Cleveland, Ohio in 1997 and extended to Kentucky roughly a decade later. The program matches up specially trained child protective services workers with family mentors (peer support specialists in recovery), behavioral health treatment providers, and the courts. The goals of the program are to ensure child safety and reduce the need for out-of-home care. A 2012 study on the impact of START on family outcomes found that mothers who participated achieved sobriety at a higher rate than those in more traditional treatment programs. Children were also placed in the custody of the state at half the anticipated rate.

- Medication-assisted Treatment (MAT) – an approach that combines medication with counseling and behavioral therapies – is a best practice, and has been linked to decreases in negative outcomes (e.g., opioid use, opioid-related overdose deaths, criminal activity, and infectious disease transmission) and increases in social functioning and retention in treatment, two factors that play heavily into improved parenting skills. MAT has also been found to be effective in providing care for pregnant women who struggle with opioid dependence. Despite some misconceptions in field out the approach, MAT has been associated with improved prenatal care, reduced illicit drug use, and better neonatal outcomes.

- Family Treatment Drug Courts (FTDCs) are specialized courts that respond to cases of abuse and neglect involving caregiver substance misuse. Using a family-friendly approach, FTDCs combine judicial oversight and comprehensive services by bridging together substance use treatment, child welfare services, community supports, and the court system. The unique model balances the rights of both children and parents and aims to create safe family environments while treating the parents’ underlying substance use disorder. In 2015, there were a reported 300 FTDCs across the country, with models and implementation varying state-to-state. The benefits associated with FTDCs include higher participation rates and longer stays in treatment (when compared with non-FTDC participants). The model also yields positive child outcomes; children reportable spend less time in out of home care and are more likely to be reunified with their parent(s).

Support for child welfare agencies and caseworkers

Child welfare agencies are first responders to families in crisis. Caseworkers can encounter stressful or traumatic experiences working with families opioid dependence, witnessing the aftermath of a parental opioid overdose is just one devastating example. That is why supporting frontline staff is imperative.

Provide Specialized Training

Reports indicate that there can be gaps in knowledge among caseworkers around the needs of families with substance use issues and the treatment of opioid use disorders. Training and support in these areas is critical for those working in the field. Additionally, specialized training around recognizing and responding to trauma and trauma-informed care practices is needed when working with families impacted by opioid abuse, as there can be long-lasting negative effects for children if trauma symptoms go undetected and untreated.

Promote Workforce Well-Being

Organizations should employ strategies to reduce secondary trauma and burnout in order to promote workforce well-being. Approaches to reducing the adverse effects of include:

- helping staff identify and manage the difficulties associated with their respective positions;

- encouraging self-care and well-being through policies and communications with personnel;

- offering positive coping skills and stress management training; and

- providing adequate supervision and staff coverage.

Encourage Systems Coordination

Families with substance use issues frequently face other risk factors. Collaboration with other service providers is crucial in helping link parents and their children to the services that they need. The surge in opioid use has trickled into a number of child and family-serving systems. As such, agencies should take steps whenever possible to develop partnerships in their communities to support the work.

Allocate Federal Resources

The crisis is too far-reaching to not have a comprehensive, coordinated federal plan of action in place. Despite declaring a public health emergency, we have yet to devote the level of funds that are needed address opioid dependence. While social service providers and child welfare agencies continue to try and mitigate the impact on a local or state level, the importance of allocating appropriate federal resources to support these efforts cannot be overlooked.

For example, the Maternal, Infant and Early Childhood Home Visiting Program (MIECHV) funds home visiting programs that aim to promote positive parenting practices and healthy parent-child interactions. These programs can also link parents struggling with substance dependence to appropriate treatment providers. Research shows that no matter what level of care is needed, the most beneficial approach is the one that treats families together. MIECHV could help address the unique service needs of the growing number families impacted by opioid dependence.

The Family First Prevention Services Act (FFPSA) may also be a way for federal resources to help child welfare agencies respond to the epidemic. FFPSA is poised to dramatically overhaul the child welfare system, putting federal dollars toward prevention programs and interventions aimed at keeping families together. Substance use treatment programs are among the services that can be prioritized through the restructuring of funds. Additionally, given the increased demand for foster care and relative caregiver placements, advocates are calling to strengthen foster parent recruitment and retention efforts and kinship navigator programs. Increasing capacity in these areas will in turn aid child welfare agencies in finding safe, appropriate placements for children impacted by the current crisis.

There are a variety of other ways that programs and policies could provide relief at a national level; however, equally important is the need for improving data collection across various systems to make informed and evidence-based decisions.

The thing about the ripple effect…

It is hard to stop once it gets put in motion. But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try. While the current crisis is overwhelming, there are proposed solutions, ones that can positively impact families and change the course for future generations.

We encourage you to share your thoughts on this important issue. How has the opioid epidemic impacted your community and the children and families you serve? What has been the response? Share your feedback in the comments below!

The accreditation process is most valuable when staff throughout the agency are engaged, but this isn’t always easy. Harris County Protective Services for Children and Adults shares the fun, interactive methods they used to promote the culture of COA and gain staff buy-in.

The phrase “THEY ARE COMING” typically strikes fear in the hearts of agency staff and leadership preparing for a reaccreditation Site Visit. Even scarier is that a lot of the staff not directly involved in the process never know exactly who “THEY” are.

Since the last Site Visit 4 years ago, our organization had experienced many changes to leadership. Our Quality Improvement Team had transitions in roles and was now staffed with a diverse team with a fresh set of eyes for COA.

As a team new to the process, one of the first things we did was an assessment of staff feelings and knowledge about COA.

Challenge #1: Even though our organization has been successfully reaccredited since 1978, staff still remained in panic mode.

When it was time for our formal Site Visit COA continued to be viewed as a separate entity, a “THEY” of sorts. We wanted to be sure that the view was of our partner helping us to identify strengths and areas for improvement in ways that may not be immediately apparent. We realized that part of the issue was that historically, we had not engaged and educated ALL staff (and not just those involved in turning in evidence). We needed to reframe staff perceptions as COA being a positive experience and focus on the benefits of the visit instead of just focusing on meeting deadlines to turn in evidence.

Challenge #2: What did we do to engage staff before? What resources do we have to engage over 19 different programs with field and on site staff?

We convened a think tank of new and seasoned staff from Quality Improvement, Communications and our Training Institute. At the last Site Visit we were only able to reach staff via email blasts and a creative “Go for the Green COA Poem.” Though staff comments about COA from past surveys and focus groups was reviewed, it was hard to track who actually opened the emails and who really took-home the message of what COA is all about.

We wanted to do something different and FUN that would appeal to our two majority generations in the agency identified from our annual staff survey: millennials and baby boomers.

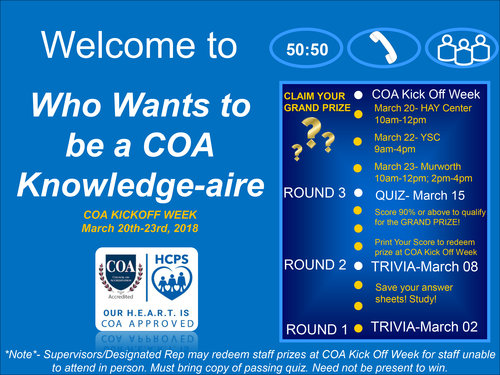

Out of our think tank was born the theme for our COA Kick Off Week online Challenge, “Who Wants To Be A COA-Knowledgaire”, which included a teaser video about COA starring our own “COA Queen” which addressed and made light of staff feelings about COA.

Teaser Video

We also found online templates for interactive Power Point Shows that were clickable to reveal correct (or incorrect, buzz!) answers that staff could complete each week to gain knowledge instead of having to read long text.

If staff passed the Grand Challenge Quiz (via Survey Monkey) with 90 or above, they were eligible to redeem limited edition swag items. The swag items, though a small investment from the Quality Improvement department ($2,000), made for an effective incentive that got many unfamiliar faces involved and increased word of mouth.

At the end of the challenge, almost 50% of our staff had participated visiting us in person at each site to collect their unique swag, a huge participation success for a governmental agency.

The Quality Improvement Team showing off their COA swag.

We have additional engagement activities planned for the months leading up to our visit to keep the momentum going and to continue promoting our Site Visit as an opportunity to showcase our programs and to learn about the up and coming best practices for social service agencies and nonprofits. To learn more about HCPS on their website and Facebook.

Resources

- Flip card Trivia

- How to make a power point show auto-run and clickable

- WHO WANTS TO BE A MILLIONAIRE GAME TEMPLATE sample template by Mark Damon

The views, information and opinions expressed herein are those of the author; they do not necessarily reflect those of the Council on Accreditation (COA). COA invites guest authors to contribute to the COA blog due to COA’s confidence in their knowledge on the subject matter and their expertise in their chosen field.

Emmony Pena

Emmony is a Licensed Master Social Worker from the University Of Houston Graduate College Of Social Work with a focus on program development and evaluation. She has 5 years of experience in Data Analysis and Process Improvement through her graduate research assistant experience at MD Anderson and in her current role as Quality Improvement Professional at Harris County Protective Services. Emmony’s goal is to engage staff in performance and quality improvement activities and in plan-do-study-check act cycles.

Emmony monitors the implementation of the agency’s Performance and Quality Improvement plan and provides technical assistance and leadership to programs in the areas of Council on Accreditation standards, data collection, logic model development, focus groups, case review audits and trainings.

Certifications: CANS Assessment (Child and Adolescent Needs and Strengths) Certified

The social and human services field might conjure images of social workers seeing clients all day in their offices or case managers out on home visits, and although these are aspects of many jobs in this field, the day-to-day reality is often a bit more varied. Social service organizations include a wide array of roles such as human resource directors, finance managers, quality improvement specialists to name a few. And even for clinicians or those in direct practice a good amount of time is spent completing paperwork and other administrative tasks. While these are critical functions of our organizations, those tasks might not be what first attracted us to the social services field. Often, the pull to work in this field comes out of a desire to “give back” or “do good”. And while all tasks in our organizations help to advance the important missions that we signed on for, some of us may still be looking for more or different ways to give back. Many of us might already volunteer for nonprofit boards, give to charity, or volunteer our skills more directly on our own time. Creating or participating in a volunteer initiative in the workplace might assist with scratching an altruistic itch and benefit our organizations at the same time.

You may have heard of the terms corporate social responsibility or corporate philanthropy and thought they weren’t relevant to your organization. The first instinct might be “Our whole function is to create social impact driven by our mission. We don’t need to/have time for/have the energy for additional volunteer work”. You might be surprised to discover that there are still opportunities and interest at your organization to incorporate the essence of these ideas. Specifically, one way is to create a space for employees to give back through volunteer initiatives. After reading on, I hope you’ll find that there are various ways in which doing so can positively reverberate through your work environment, from boosting morale to encouraging closer work with the community you serve.

What are the benefits?

I think it’s hard to overstate the benefits of creating a space for employee volunteerism. For fun, let’s frame it in the context of some COA standards. After all the standards outline best practice!

Human Resources (HR) and Personnel Development and Training (TS)

Staff satisfaction and retention is an area that challenges many organizations in our field. Creating workplace initiatives that keep staff connected to each other and the organization’s mission is one way to help address this. Employee volunteerism initiatives can be a great benefit or perk to highlight for recruiting purposes and to raise morale for current staff. It might be challenging to increase pay or vacation time, but maybe your organization can consider allowing employees time for volunteer activities.

The opportunity to volunteer as a team, department or organization also serves as an opportunity for team building, or dare I say “bonding”. Getting outside the walls of your office and the routine of your day-to-day can allow you to get to know your co-workers in a new light and increase cross-departmental collaboration and relationships.

It also provides an opportunity to develop and demonstrate skills that you might not otherwise have occasion to use while at work. Participating in something different than typical day to day activities can allow opportunities for a newer or more junior staff member to shine in their leadership skills if given the opportunity. Staff might also have an opportunity to develop skills while volunteering. Maybe you can even consider sponsoring an external volunteer organization to come in to train your staff. Some organizations here in New York City require a one-day training in order to volunteer with them. If staff are able to get that training together and through work, it opens up the opportunity for them to volunteer together or on their own.

Community involvement (GOV / AFM)

Another great benefit of volunteering in your local community is the opportunity for community involvement and creating perhaps unexpected partnerships that raise awareness of your mission and presence in the community. You aren’t doing this for PR, but often increased community connections and awareness of your brand is an added benefit. If you have tee-shirts or hats with your branding, and it feels appropriate, you can ask staff to wear them while volunteering to build name recognition.

An event that takes place outside of normal work hours but can be a great opportunity for staff to come together is participating in a walk or fundraiser. Perhaps your organization sponsors a team for a charity walk and then gets outside together on a weekend to participate. Maybe your nonprofit can even offer to trade with another nonprofit and partner to volunteer for each other one day a year. You never know what unexpected relationships can be born out of volunteerism.

One other outside the box idea is if your organization sponsors conferences or events, can you incorporate an aspect of giving back? Maybe an optional day tagged onto the end of a conference for a volunteer activity?

Performance Quality Improvement (PQI)

Lastly, of course – this is COA – we have to tie it to PQI! One way you might consider looking at creating volunteer opportunities at your organization is to incorporate it into your PQI initiatives. If staff express interest, this absolutely works in relation to any of the areas listed above and tied into goals around staff retention, community awareness, or cross-departmental collaboration, for example.

Show me the data

Speaking of PQI, of course in this day and age, you want your decisions to be supported by stats and data. Well, lucky for you, we’ve got it:

- A 2017 Deloitte Volunteerism Survey of working Americans found that 88% of respondents believed that companies who sponsor volunteer activities offer a better overall working environment than those who do not.

- Research from the University of Georgia, supports the fact that employee volunteering is linked to greater workplace productivity.

- America’s Charities Snapshot 2017, is a great resource for data related to “What U.S. Employees Think About Workplace Giving, Volunteering, and CSR”. Their CEO Jim Star, states “Employers who build programs that connect workers to each other, expose them to corporate leaders, and give them meaningful ways to make a difference in their communities send a strong statement to those workers that they are valued. They also build stronger teams and deeper relationships.”

- COA’s nonscientific staff survey showed similar results: When asked to share what they liked best about COA volunteer opportunities, 88% indicated that it “promotes team-building and builds camaraderie.”

COA – Practice what you preach

Here in lower Manhattan at the COA offices, we think this is one area where we definitely walk the walk. After Hurricane Sandy hit the East Coast and New York City hard in 2012, COA staffers spent a day on Staten Island cleaning out a home affected by the storm. Even for those of us in New York who lived through it, the impact of seeing the devastation to that part of the city was sobering. It also was a wakeup call that we as staff were eager to give back outside of our day to day work, and appreciated the opportunity to get out of the office, roll our sleeves up, and interact with our community. After that event, staff expressed (through our staff suggestion box!) that COA should formalize an employee volunteer initiative. The COA Volunteer Committee was born out of this experience.

To date, thanks to dedicated staff and support from COA leadership, the COA Volunteer Committee has been up and running for over five years. Highlights include reading stories to kids, chaperoning an urban garden project, cleaning up Governors Island, shucking corn for a food bank, lending our hands for a meal delivery organization, donating to coat and backpack drives, and more.

The internal response to these initiatives has been overwhelmingly positive. On staff surveys, we’ve heard feedback like “The volunteer activities promote team-building, a sense of community and positively contribute to staff morale”, “generates collaboration” and, our favorite – it gives “the warm fuzzies”.

Helpful tips

To leave you with some tips from our experience:

- Get buy-in from the top: As with many things, buy-in is key. Leadership endorsing and participating is a key factor in your volunteer efforts success. Lead by example.

- Staff input: Before you make a decision about your volunteer activities, it helps to get a sense of what people are interested in. You might create a simple staff survey to get input and specific suggestions, and then figure out what is the best fit for your audience.

- Variety: If you work for an organization focusing on children, maybe one year you volunteer to plant trees or weed a community garden. If you work in adult substance use, maybe arrange to spend an afternoon reading to kids.

- Risk prevention: You’ll want to consider any risks that may be associated with the planned activity and take steps to mitigate those risks. Setting some simple but clear guidelines for participants is a good way to make sure everyone has clear, shared expectations. A few you might think to include are dress code expectations, time commitment, meeting spots, and communication protocols for off-site, to ensure everyone is on the same page from the start.

- Closing the loop!: A post-activity survey or debriefing to capture what people liked and didn’t like about the activity (or for those who didn’t, what hampered their participation), can give you great insight into what to look for next time.

In the end, only kindness matters

Clearly, there isn’t a one-size-fits-all approach when it comes to volunteer initiatives for social and human service organizations. What works at one organization, might not be a fit at another. However, based on the data, as well as our experience at COA, I encourage you to give some thought and get creative about how this might look for your organization. Maybe start small with just your team or department sponsoring a coat drive this year. Or, some of you may already have robust volunteer initiatives in full swing at your organizations. We’d love to hear about workplace volunteer efforts you may have participated in or put into place at your organization. Please share any questions, thoughts or success stories below!

Dr. Robert Block, former president of the American Academy of Pediatrics, has been widely quoted as saying, “Adverse childhood experiences are the single greatest unaddressed public health threat facing our nation today.” That is a statement that many would agree holds true at this very moment, and one that cannot be ignored.

April is child abuse prevention month, and there is no better time to raise awareness around the long-lasting effects of child abuse, neglect, and other types of childhood trauma. This article will explain Adverse Childhood Experiences, share relevant findings from the CDC-Kaiser Permanente Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study, and explore how to put science into practice in order to mitigate the impact of early adversity and toxic stress.

What are Adverse Childhood Experiences?

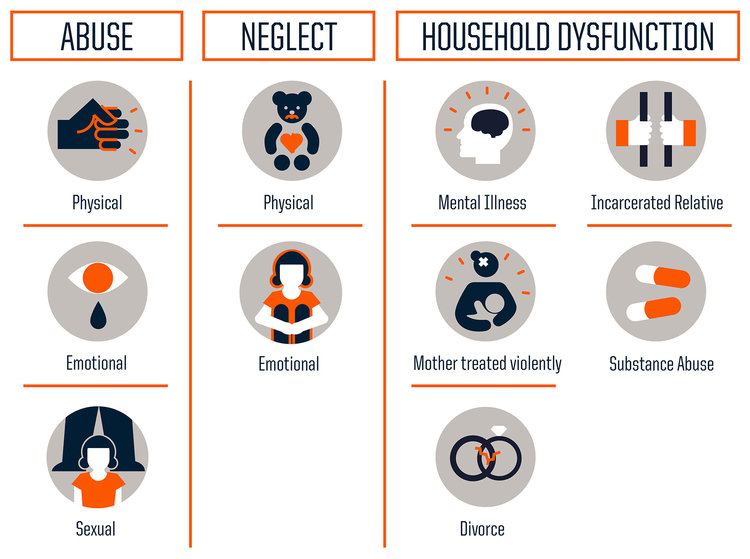

Adverse Childhood Experiences or ACES are traumatic early life events that can lead to negative health outcomes as adults. Much of what we know about ACEs stems from the CDC-Kaiser Permanente Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study, conducted between 1995 and 1997, which examined 10 types of childhood trauma and their impact on long-term health and well-being. Researchers identified three categories of childhood trauma: abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction. The findings were shocking.

The study concluded that the more adversity one experiences earlier in life, the greater the risk of significant physical, emotional, and social consequences in the future. Now, you may be thinking – Why is that so shocking? A difficult upbringing being linked to hardships down the road, what is groundbreaking about that? Well, it is the prevalence at which ACEs occur, and in turn the impact that has on the population. Studies are often criticized for their self-selecting biases, however this investigation challenges that concern. The 17,000+ study participants were predominantly white, middle- and upper-middle class; most were college-educated and had stable jobs and heath care. They represent a group that we don’t typically associate with adversity, showing that trauma has no boundaries and is more common than we think.

Let’s break it down…

Everyone has an ACE score of 0 to 10, with each type of trauma counting as one regardless of the number of times it occurs.

According to the study, nearly two-thirds (64%) of adults have experienced at least one type of childhood adversity. ACEs increase the risk of: chronic disease and health issues, mental illness, engaging in risky behaviors (smoking, substance misuse, and unsafe sexual activity, for example), inadequate social skills, poor academic achievement and/or work performance, and intimate partner violence. The study also showed that ACEs cluster, meaning that if you have one there is a good chance (87%) that you have another. Almost 40% of participants reported two or more ACEs and roughly 12.5% experience 4 or more ACES. The higher your ACE score, the worse the outcomes.

When you look at each type of trauma and look at the prevalence of specific ACEs, the most dominant ACE experienced by participants was physical abuse (28%), followed closely by having a family member with a substance use disorder (27%). However, it is important to note the type of trauma does not impact the outcome per say. To the brain stress is stress; therefore, it doesn’t matter what type of adversity you face, the health consequences will be the same.

When a child experiences trauma, their cognitive functioning and ability to cope with tricky and icky (technical terms) emotions are compromised. Repeated exposure to traumatic events in childhood or prolonged adversity without appropriate adult/caregiver supports negatively affects the way the brain develops and functions; this is known as toxic stress. Toxic stress can be harmful on one’s physical and mental health, yielding undesirable outcomes later in adolescence and adulthood.

Why does this occur? Stressful or traumatic events early in life have a direct impact on a child’s brain development. The brain experiences rapid changes during the first five years, especially from birth to age three. During this informative time, the brain and its neural pathways are susceptible to external factors. While occasional stress is part of a child’s healthy development, chronic stress can negatively affect learning, growth, and behavior. This is in large part due to the overload of stress chemicals and their influence on the brain. When we feel threatened, the body activates our stress response systems and releases stress hormones (e.g., adrenaline and cortisol). Stress reactions and chemicals are meant to protect us, but too much can have the opposite effect. Enter toxic stress. Extended activation of stress response systems in early childhood can disrupt the structure of the brain and the way it communicates with the body, which can lead to major health issues in the future.

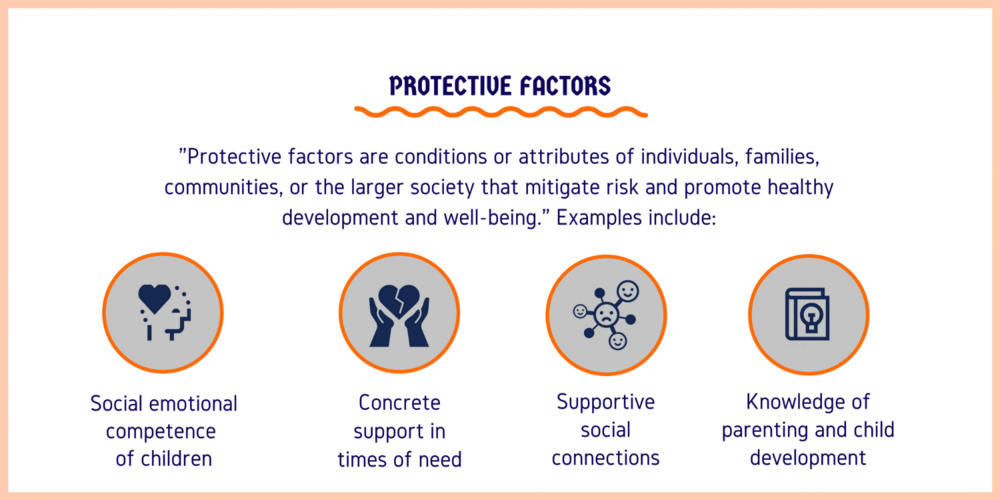

Building resilience

The brain is constantly changing in response to the environment; it is kind of like a chameleon in that way. This adaption is key to facilitating positive change in the face of toxic stress. Creating safe, stable, nurturing relationships and environments are critical to mitigate and prevent the consequences of childhood adversity. While ACEs have the potential to be long-lasting, they don’t have to be; we have the tools to help children thrive in the face of adversity and go on to meet their full potential.

A strong (and continuously growing) literature base has demonstrated that building resilience can help negate stress-induced changes in the brain. Resilience is the “process of adapting well in the face of adversity, trauma, tragedy, threats or significant sources of stress”. Experts in the field of child trauma convey that one of the biggest determinants in being resilient is having nurturing and supportive relationships with adults in one’s family and community. Dr. Bruce D. Perry, a childhood trauma guru, considers “the more healthy relationships a child has, the more likely he will be to recover from trauma and thrive.” And it’s true, adult-child relationships play a significant role in helping children cope with challenges. If stress reactions are time-limited and buffered by protective adult relationships, a child is able to recover and learns how to adapt in difficult situations. That is why high-quality, evidence-based parent education, home visiting programs, and parenting practices are so important. These interventions emphasize the power of familial relationships, caregiver bonding, and positive social interactions. Just as critical are protective factors and their role in strengthening families and preventing trauma. Studies have shown, and continue to investigate, the ways in which different protective factors promote optimal child development. And while intervention can occur at any time – there is no magical cut-off age – there is clear evidence that shows the earlier the better.

There is hope

It’s true that the findings from the ACE Study don’t leave you feeling warm and fuzzy. In fact, at this point, you may be wondering if there is any hope or if we are all doomed. Fear not! This is actually the exciting part (hear me out…).

The ACE Study findings are paving the way for innovative solutions to a public health crisis. It’s cutting across sectors and systems to bridge services and advocacy, and encouraging individuals and groups to collaborate and communicate like never before. From pediatricians to social workers, people in communities nationwide (and internationally) are using ACEs science to join forces and better the lives of children and families. Here are just a few examples:

- The Center for Youth Wellness developed an ACEs screening questionnaire and protocol for pediatric care providers to target more effective early intervention strategies.

- In Manchester, NH, a joint-response team a – Adverse Childhood Experiences Response Team (ACERT) – is bringing together law enforcement, mental health professionals, and community providers to respond to the service needs of children who have been exposed to violence.

- Lincoln High School in Walla Walla, WA incorporates ACEs into their work with students, more specifically their approach to school discipline.

- Trauma-free NYC, a university-community partnership, aims to raise awareness of ACEs and design and promote training and learning opportunities for the larger NYC community.

- Community members and practitioners in Raleigh, NC came together to watch a film about the science of ACEs, Resilience, and have an in-depth discussion around how systems can better address children who have experienced trauma.

A call to action

In her 2014 TED talk on childhood trauma, Dr. Nadine Burke Harris closed in saying, “The single most important thing that we need today is the courage to look this problem in the face and say, this is real and this is all of us. I believe that we are the movement.” Indeed we are. We are the change makers that can combat the effects of childhood adversity. Knowing what we now know, how do we move forward?

Continue to raise awareness

We must continue to raise awareness, not just of the long-term outcomes assocaited with childhood trauma, but also the power of early intervention. Recently, 60 Minutes did a piece on the impact of childhood trauma, highlighting the impactful work of organizations like SaintA and Nia Imani Family, Inc.. The eye-opening conversation was facilitated by Oprah Winfrey…yep, Oprah. The importance of stories like these in mainstream media cannot be understated. We know that when Oprah talks, people listen. Look at the traction that this one segment has gotten over the past month. It’s been invigorating.

Want another example? Sesame Street collaborated with the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation to launch an initiative to help children manage traumatic life experiences. Who better to take on the task than the beloved Sesame Street Muppets? The characters are loved by children and adults alike. An array of research-driven materials have been created through the partnership and are available to children, parents, and professionals. The content is truly original and inspired – it even includes Muppets modeling coping strategies – and emphasizes the power of resilience in the face of adversity.

Now, recognizing that we all don’t have access to Oprah, Big Bird, or a national TV network (wouldn’t that be awesome though?), it is important to take to the platforms we do have at our disposal to spread our message. Post an article on your organization’s Facebook page, email your colleagues, tweet at your community partners…Connecting with diverse audiences ignites new and ongoing conversations around where we are, what we know, and what we can do.

Become trauma-informed

Trauma-informed care is no longer the exception, but instead the expectation. It’s about reframing the conversation from “What’s wrong with you?” to “What happened to you?” There are a great deal of resources out there that provide excellent guidance on becoming trauma-informed, both in clinical practice and at the organizational level. Here are a few that you may want to check out:

- ChildTrauma Academy

- Child Welfare Information Gateway – Trauma-Informed Practice

- National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN)

- National Center for Trauma-Informed Care and Alternatives to Seclusion and Restraint (NCTIC)

Promote shared learning

Many in the field have been advocating for the implementation of programs and policies that address ACEs, calling for more data and additional research to better target prevention efforts and supports. The fact is that while the ACEs may be new to some, others have been implementing innovative trauma-informed, resilience-building practices in their everyday work to create positive change. We have presented a few examples, but there are many more being spearheaded by individuals, organizations, systems, and communities nationwide. Shared learning is crucial to creating and maintaining a movement.

Be part of the movement

And with that…we want to hear from you. What do you think about the ACE Study and the findings? How are you addressing the needs of children and families who have experienced trauma? Are you implementing innovative trauma-informed practices at your organization?

Share your thoughts in the comments below!

A big thank you to Stan Capela of Heartshare Human Services of New York for this guest post!

My name is Stan Capela and I have been a COA Peer Reviewer and Team Leader since 1996. By the end of April, I will have completed 112 Site Visits. At the glorious age of 65 after devoting 40 years to the field of social services, I’m beginning to reflect back on my journey. I want to share my experiences with you in honor of Volunteer Month.

Before I share my story let me give you a snapshot of a Volunteers numerous responsibilities. First you are assigned a Site Visit. I started as a Peer Reviewer, working with a team of colleagues to review an organization. Ten years ago, I became a Team Leader and gained more responsibilities such as; making contact with the organization, setting up travel for the Peer Review team, developing the Site Visit schedule, assigning standards sections to the Peer Reviewers, and leading the entrance and exit meetings where the team interacts with the organization. The latter gives the Peer Review team a chance to introduce themselves to the organization and provide information about how the review will take place.

Wait! I’m getting ahead of myself. The entire review process begins with a Self-Study submitted by the organization and reviewed prior to their Site Visit. When the review team arrives on-site most of their time is spent reviewing case records, policies and conducting interviews. By the time the exit meeting occurs, the Team Leader and review team are ready to provide an overview of the organization’s strengths and challenges. If you want to learn more about the Site Visit process then I recommend reading Recipe for Conducting Quality Accreditation Site Visits which I co-authored with Joe Frisino, a member of the COA Standards Development team, in New Directions for Evaluation.

The decision to become a COA Volunteer starts with the simple question, why? And traveling through my many memories leads me to that answer.