If someone were to rate their wellness level, their first instinct might be to measure their physical or mental health against common indicators, such as the presence of an illness or injury. These markers are a good place to start, but one’s health status does not happen in a vacuum independent of their environment.

As the United States continues to find its healthcare system under fire, one issue many point to is the health disparities mediated by race, ethnicity, geography, orientation, socioeconomic status, etc. Both level of education and socioeconomic status have direct correlations to health status, with individuals living in poverty eight times as likely to have poor health outcomes. As recently as April 2018, the New York Times reported on significantly high mortality rates for America’s Black mothers and babies in comparison to their white counterparts and how that relates to their lived experience.

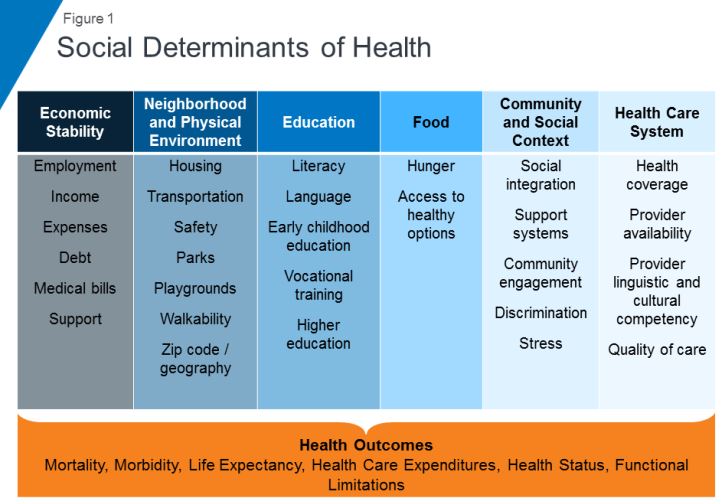

Often times your health is influenced by factors beyond the individual’s control, factors related to their social context. Health professionals refer to these as social determinants of health (SDOH) and they have become the focus of increasing interest when it comes to closing the health disparity gap and taking more proactive approaches to population health and well-being.

Defining SDOH

SDOH refer to economic and social conditions and their distribution among the population thus influencing individual and group differences in health status. They are factors found in one’s living and working environments rather than individual risk factors such as behavior or genetics, which can impact one’s vulnerability to disease.

The Center for Disease Control (CDC) and the World Health Organization (WHO) have both emphasized the importance of taking into consideration the conditions in which people live, learn, work, and play when assessing health status. WHO frames the potential for these experiences to be health-damaging as “the result of toxic combination of poor social policies, unfair economic arrangements, and bad politics,” calling for society to look beyond the health sector when dealing with issues of health and disease.

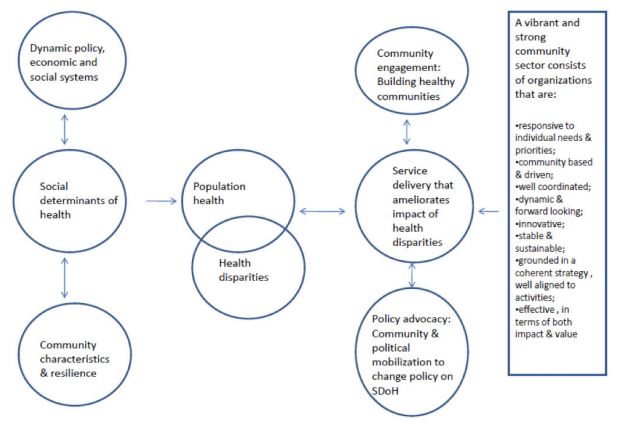

Audrey Danaher, from the Wellesley Institute, created a framework to describe how these social determinants may play upon each other given that the impact is not direct, but mediated. For instance, community characteristics and resilience can have an effect upon SDOH independent of policy, economic, and social systems. A responsive community sector (e.g. non-profit organizations that provide services within communities to meet needs) can help to reduce the disparities through engagement, advocacy, and service delivery. It is worth noting that Danaher’s data and framework comes from communities in Canada, which has universal, single-payer healthcare, further supporting the argument that individual health goes beyond just healthcare.

SDOH on individuals’ health

SDOH play a significant role in individuals’ health outcomes, and research has demonstrated that there is a social patterning of disease. Per Williams, Sternthal, and Wright (2009), “disadvantaged social status predicts higher levels of morbidity for a broad range of conditions in both children and adults.” Growing up in economic poverty in and of itself is correlated with a broad range of health-damaging conditions (e.g., family turmoil, neighborhood violence, consume polluted water and air) and growing up as part of a marginalized community increases your exposure to psychological stressors. But how do these things in turn play a role in individuals’ health?

Let’s look at asthma. While the consumption of polluted water and air increases the risk of asthma within the population, this alone does not fully account for this disparate distribution childhood asthma. In a 2017 study, researchers found that African-American children living in lower socioeconomic neighborhoods were 8.8% more likely to have asthma than their white counterparts, 6.7% more likely in middle-class neighborhoods, and 5.8% more likely in affluent communities. Not only are there differences among racial lines, but youth in more deprived communities are significantly more likely to have asthma emergency department visits and significantly more asthma inpatient admissions. Some SDOH identified as playing a role in these group differences include maternal stress during pregnancy, living in communities with higher levels of violence, overburdened or absent social supports, and psychological morbidity.

Another example of a SDOH is food insecurity, defined by the U.S. Department of Agriculture as a lack of access to enough food for an active, healthy life. Food insecurity is caused by a number of elements such as income and unemployment, disability, and food deserts, which are associated with both socioeconomic status and race/ethnicity. Food insecurity does not necessarily cause hunger, although it is a possible outcome, but it is tied to chronic disease such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes.

Community sector in action! Connecting SDOH to service delivery

Community sector initiatives have often taken the lead in responding to deprivation and negative SDOH. Due to the nebulous nature of SDOH and how they’re specific to different communities and populations, it makes sense that change comes from within the community itself. Just as communities can be a cause for poor SDOH, they can also be the catalyst for improving them and thus improving the community’s outcomes.

Majora Carter’s environmental justice work in the South Bronx is an excellent example of a community-driven response to SDOH. The South Bronx is home to a significant number of industrial plants, including waste processing (40% of the city’s waste and 100% of the Bronx’s end up there), sewage treatment, and four electrical power plants. It has the lowest ratio of parks to residents throughout the entire city; it ticks all the marks on social determinants of health listed above as well as the poor corresponding outcomes. Carter started with the goal of creating a new park, which subsequently led to a greenway movement. One of her next moves was to secure funding for a waterfront esplanade that allowed for a wider range of forms of transportation, thereby influencing policy on traffic safety in the area. Using social capital, she also created facilities that would not only bolster the health of residents in the community but improve quality of life (e.g., encourage residents to be more active) and create opportunities, such as green-collar jobs and community business investment. By recognizing and focusing on the impact of the environment on the health and safety of its inhabitants Carter was able to develop solutions to improve the health of her neighbors.

Carter’s success is not isolated. COA accredited organizations are the community sector and often occupy the spaces needed to rehabilitate SDOH. While this not has always been an explicit or even conscious goal of human and social service delivery, if you look at the SDOH listed in the graphic above, you can map the services provided by COA accredited organizations onto the list. Whether it’s providing youth with alternatives to out-of-school suspension, offering assistance with navigating the healthcare system, or providing housing and community resources in a supported living program, all of these solutions fill gaps in the community and boosts their SDOH.

Next steps

This wouldn’t be a COA blog post without a few ways in which you can get involved. Here are a few initiatives working to improve social determinants of health:

One of the most powerful actions you can take is to get involved with your own community. What are some of the issues you see around you? What are some of the areas that need further support? Are there grants from your city to help implement the changes needed? Chances are, there are already organizations working towards improving community health outcomes with opportunities to volunteer or partner.